Click here to return to Blog Post Intro

W.E.B. Du Bois said, “What are these songs, and what do they mean? They are the music of an unhappy people, of the children of disappointment; they tell of death and suffering and unvoiced longing toward a truer world.”

Dyson asks, “How can we possibly combat the blindness of white men and women who are so deeply invested in their own privilege that they cannot afford to see how much we suffer? But most of all, Oh God, how can we keep racism from strangling every bit of hope left in our bodies and minds?”

He goes on to say, “The complicity of even good white folk who claim that they care, and yet their voices don’t ring out loudly and consistently against an injustice so grave that it sends us to our graves with frightening frequency. They wring their hands in frustration to prove that they empathize with our plight—that is, those who care enough to do so—and then throw them up in surrender. What we mostly hear is deafening silence. What we mostly see is crushing indifference. Lord, what are we to do in a nation of people who claim to love you and hold fast to your word and way and yet they let their brothers and sisters murder us like we are animals?”

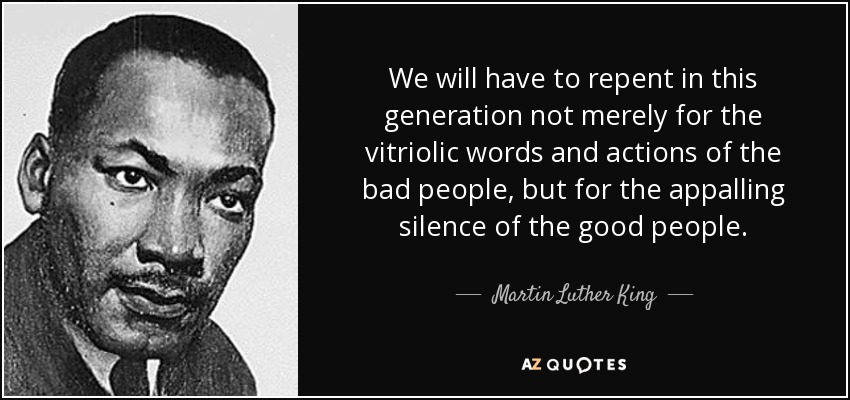

Martin Luther King, Jr. once asked, “Do you know that a lot of the race problem grows out of the need that some people have to feel superior. A need that some people have to feel that their white skin ordained them to be first.” Early in his career King believed in the essential goodness of white America. He trusted most whites to put away their bigotry in the face of black suffering. In the last three years of his life, he grew far more skeptical of the ability or willingness of white folk to change. He concluded, sadly, that most whites are unconscious racists and that black suffering generated a “terrible ambivalence in the soul of white America.”

In 1967, King declared that the “fact is that there has never been any single, solid, determined commitment on the part of the vast majority of white Americans…to genuine equality for Negroes.” And just two weeks before his death, he announced, with a broken heart, “Yes it is true…America is a racist country.”

Repenting of Whiteness

Inventing Whiteness

Dyson opens with “an ugly secret: there is no such thing as white people. Race has no meaning outside of the cultures we live in and the worlds we fashion out of its force and energy. Whiteness is an advantage and privilege because you have made it so, not because the universe demands it. Whiteness has privilege and power connected to it, no matter how poor you are. Whiteness is slick and endlessly inventive. It is most effective when it makes itself invisible, when it appears neutral, human, American. The only way to save our nation, and, yes, to save yourselves, is to let go of whiteness and the vision of American history it supports.”

What so often passes for American history is really a record of white priorities or conquests set down as white achievement. The winners write history. To say this out loud, in this day and age, when whiteness has congratulated itself for its tolerance of other cultures and peoples, is to invite real resistance from white America.

Dyson pleads, “My dear friends, please try to understand that whiteness is limitless possibility. It is universal and invisible. That’s why many of you are offended by any reference to race. You believe you are acting and thinking neutrally, objectively, without preference for one group or the next, including your own. You see yourselves as colorless until black folk dump the garbage of race on your heads. Can’t you see, my friends, that whiteness is determined to get the last word? That it is determined once again to make its unspoken allegiances and silent privilege the basis of justice in America? Don’t you see it’s your way or no way at all? Please don’t pretend you don’t understand us. Being white means never having to say you’re white. Whiteness long ago, at least in America, shed its ethnic skin and struck a universal pose. Whiteness never had to announce its whiteness, never had to promote or celebrate its unique features. There is a paradox that many of you refuse to see: to get to a point where race won’t make a difference, we have to wrestle, first, with the difference that race makes.”

The Five Stages of White Grief

There is often sorrow and anguish in white America when blackness comes in the room. It gives one a bad case of what can only be called, colloquially, the racial blues, but more formally, let’s name it C.H.E.A.T. (Chronic Historical Evasion and Trickery) disorder. This malady is characterized by bouts of depression when you can no longer avoid the history that you think doesn’t matter much, or when your attempts to deceive yourself and others—about the low quality of all that isn’t white—fall flat.

If not treated early on, C.H.E.A.T. leads to other disorders, including:

- A.K.E. – Finding Alternative Knowledge Elusive

- O.O.L. – Forsaking Others’ Outstanding Literacy

- I.E. – Lacking Introspection Entirely

The only way for you to overcome C.H.E.A.T. is to confront the disorder head-on and acknowledge the five stages of white racial grief that you experience as you grapple with the presence of black folk and the history they created—and the very way they have changed American society:

- The first stage of white racial grief is to plead utter ignorance about black life and culture. White America, you deliberately forget how whiteness caused black suffering. And it shows in the strangest ways. You forget how you kept black folk poor as sharecroppers. You forget how you kept us out of your classrooms and in subpar schools. One of the great perks of being white in America is the capacity to forget at will. The sort of amnesia that blankets white America is reflected in an Alan Bergman and Marilyn Bergman lyric sung by Barbra Streisand: “What’s too painful to remember we simply choose to forget.”

- The second stage of grief flashes in the assertion “it didn’t happen.” Instead of “forget it,” there is “deny it.” It is best to think of systems and not individuals when it comes to racial benefit in white America. The institutions of national life favor your success, whether that means you get better schools and more jobs, or less punishment and less jail. Not because you’re necessarily smarter, or better behaved, but because being white offers you benefits, understanding, and forgiveness where needed. No one is responsible. All we hear is the refrain from reggae star Shaggy’s hit, “It wasn’t me.” We end up with what social scientist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva calls “racism without racists.” A recent study by the Public Religion Research Institute shows that 56 percent of Millennials think that the government spends too much on black and minority issues, and an even higher number think that white folk suffer discrimination, and it is just as big a problem as that suffered by black folk and other minorities.

- The third stage of white racial grief, appropriation, looms everywhere. If black history can’t be forgotten or denied, white America can, simply, take it. Appropriation is a tricky symptom of white racial grief, and one that, ironically, defers to black culture even as it displaces it. White culture bows at the shrine of black culture in order to rob it of its riches. White America loves black style when its face and form are white. Jacobs exposed his unconscious bias when he, of course, tried to claim the opposite: “I don’t see color or race—I see people.” Too bad that so many white folk believe that pretending not to see race is the way to address racism, and that when they get caught seeing race for their advantage—as in using the natural hairstyles of black folk—they claim not to see race to their advantage. The civil rights movement that inspired King, that he inspired in turn, has been appropriated too, and often in troubling ways. We end up with a greatly compromised view of the black freedom struggle. The failure to see color only benefits white America. A world without color is a world without racial debt. One of the greatest privileges of whiteness is not to see color, not to see race, and not to pay a price for ignoring it, except, of course, when you’re called on it. But even then, that price pales, quite literally, in comparison to the high price black folk pay for being black.

- The way of the racial revisionist, when it comes to black life, is, simply, to rewrite history. Their motto is, “It didn’t happen that way.” There is a flood of writing that tells us that the Civil War wasn’t really about slavery but about the effort to defend states’ rights. But, my friends, you’ve got to put yourself in our place and see the absurdity of such a claim. Defend the right of the state to do what? To enslave blacks. But even here the irresistible logic of whiteness, that is, irresistible to whites themselves—and to all of us who are subject to white whim—springs into full action.

- The urge to rewrite black history occasionally gives way to the final stage of white racial grief, which is, simply, when it comes to race, to dilute it. That is, to argue that bad stuff doesn’t just plague black folk. To summarize: “Bad stuff happens to everyone.” It is the same “me too” impulse that flares in the bitter battle against affirmative action. You never stop to think how the history of whiteness in America is one long scroll of affirmative action. You never stop to think that Babe Ruth never had to play the greatest players of his generation—just the greatest white players. You never stop to think that most of our presidents never rose to the top because they bested the competition—just the white competition. White privilege is a self-selecting tool that keeps you from having to compete with the best. You’ve been handed a history where you got most of the land, made most of the money, got most of the presumptions of goodness, and innocence, and intelligence, and thrift, and genius—and just about everything that is edifying and white. So it’s hard to stomach your gripes about the few concessions—surely not advantages—to black folk and other folk of color that are suggested in affirmative action. American history is the history of black subjugation. The Constitution is a racially hypocritical work of genius. The north and the south are divided because of us. The history of the twentieth century in America is the history of our struggle against white America.

The Plague of White Innocence

A lot of white people don’t want to confront these issues, and as a result, we end up reinforcing white fragility. White fragility is the belief that even the slightest pressure is seen by white folk as battering, as intolerable, and can provoke anger, fear, and, yes, even guilt. White fragility, as conceived by antiracist activist and educational theorist Robin DiAngelo, at times leads white folk to argue, to retreat into silence, or simply to exit a stressful situation.

When many white folk disagree, or feel uncomfortable, they get up and walk out of the room. The idolatry of whiteness and the cloak of innocence that shields it can only be quenched by love, but not merely, or even primarily, a private, personal notion of love, but a public expression of love that holds us all accountable. Justice is what love sounds like when it speaks in public.

Whites know that through institutionalized means they have the power to take black life with impunity. It’s the power of life and death that gives whiteness its force, its imperative. White life is worth more than black life. This is why the cry “Black Lives Matter” angers whites so greatly, why it is utterly offensive and effortlessly revolutionary. It takes aim at white innocence and insists on uncovering the lie of its neutrality, its naturalness, its normalcy, its normativity.

Whites ought to be honest about how they benefit from getting a good education and a great job because of whiteness. There is a big difference between the act of owning up to one’s part in perpetuating white privilege and the notion that you alone, or mostly, are responsible for the unjust system we fight.

There has been a great deal of talk, and no small consternation, about the idea of white privilege, the unspoken and often unacknowledged advantages that white Americans enjoy. And many resent such talk, thinking it is foolish.

Institutional racism is a system of ingrained social practices that perpetuate and preserve racial hierarchy. Institutional racism requires neither conscious effort nor individual intent. Minority students, like those Dyson teaches at Georgetown, are more often beset by economic and social forces than overt efforts to deny them equal education. Racial profiling is another strain of institutional racism. It is the belief that a person’s racial identity, and not their behavior, is a legitimate reason to be suspected by the police of criminal activity.

For many, what it means to be white is what it means to be American, and vice versa; your American identity is indissolubly linked to your whiteness. It is a possessive whiteness, too, one that hogs to itself the meanings of democracy.

The great black poet Langston Hughes grieved in verse, “There’s never been equality for me, nor freedom in this ‘homeland of the free.'” Martin Luther King, Jr., said that America “is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.”

Baldwin offends whites greatly because he insists on separating whiteness from American identity.

Nationalism is the uncritical celebration of one’s nation regardless of its moral or political virtue. It is summarized in the saying, “My country right or wrong.” Nationalism is the belief that no matter what one’s country does—whether racist, homophobic, sexist, xenophobic, or the like—it must be supported and accepted entirely.

The players in football and basketball may be overwhelmingly black—and in the case of baseball, increasingly Latino—but the front offices of major American sports are a white man’s game. In 2016, just 22.2 percent of professional administrator positions on National Football League teams were held by people of color. In the NFL’s league office, only 9.4 percent of those with management positions were black in a league where nearly two-thirds of its players are black.

White innocence may be a burden to whites, a burden to the nation, a burden to our progress. It is time to let it go, to let it die in place of the black bodies that it wills into nonbeing. In its place should rise a curiosity, but even more, a genuine desire to know and understand just what it means to be black in America.

Our Own Worst Enemy?

Nigger is the white man’s invention; the gender is deliberate here, since this was a white male creation even as white women shared the culture of derision too. Nigga is the black man’s response since black men were most easily seen as nigger. But black women bore an even greater burden with a double portion of slander when they were called “nigger bitch.” Nigger taps into how darkness is linked to hate. Nigga reflects self-love and a chosen identity. Nigga does far more than challenge the white imagination. Nigga also captures class and spatial tensions in black America. Nigga is grounded in the ghetto.

Too many whites believe that it is easier to warn black folk not to use the word nigga—to tone down their lyrics and eliminate a troubling word—than it is to keep white folk from using a racist epithet that still echoes in white quarters.

The fact that too many white folk don’t know the difference between nigger and nigga is more than a lack of curiosity; it is a refusal to learn about black life and culture.

Coptopia

Some whites seem genuinely surprised that most black folk fear the police. They think that blacks must have done something wrong to provoke such remorseless cruelty. And yet blacks have exhausted themselves by telling whites how police mistreat them so routinely that it is accepted as the way things are and will always be.

Do whites have “the talk” with kids to warn them within an inch of their lives not to sass the police for fear that they will return home to you in a body bag? Many of you have no idea of this level of anguish. Maybe you think that if blacks merely obey the cop’s commands he or she won’t feel threatened, won’t view them as the roadblock to their return home that night. You think that if blacks keep themselves in check nothing bad will happen.

Have you not seen how no matter what they do, the cops come for black people? That no matter how pleasant the speech, how lowly the spirits, how tame their bodies, how domesticated their gestures, blacks are read as a menace and threat by so many cops? “I feared for my life,” many cops who have shot unarmed black folk have said. Not a gun in sight. No attack in the offing. And yet blacks are consistently, without conscience, cut down in the streets. Can you honestly say that if we just comply with the cops’ wishes that we’ll be safe? How many more black folk do you have to see get sent to their deaths by cops while doing exactly what they were told before you’ll believe us?

The police have never been neutral. From the start, the policeman was not there to protect or serve, but to protect and serve whites, which often meant getting rid of us. The nation got up slave patrols to bring back the enslaved who ran away—to stop, question, and frisk them, just like many of us are treated today, to monitor, search, and arrest them, to beat them down when they were recaptured.

When slavery ended, the slave patrols ceased, but the need to police black space did not, so the Klan and police squads rose up in their place. Whites cannot know the terror that black folk feel when a cop car makes its approach and the history of racism and violence comes crashing down. The police car is a mobile plantation, and the siren is the sound of dogs hunting us down in the dark woods.

The way blacks feel about cops is how many whites feel in the face of terror. Most whites say nothing, and the silence is not only deafening, it is defeating. And when there is white response, it is often white noise, inane chatter accompanied by the wringing of white hands. There is white frustration at just how complex the problem is

In looking at the forces that might have provoked the evil in Dallas, Leon H. Wolf argued that there’s “a reality that we don’t often talk about—that societies are held together less by laws and force and threats of force than we are by ethereal and fragile concepts like mutual respect and belief in the justness of the system itself.” Wolf said it is impossible for the police to do their jobs without the vast majority of citizens believing that our society is basically just and that the police are there to protect them. Wolf asked us to imagine what might happen if a subcommunity perceived that those bonds had dissolved in application to them.

Dara Lind cogently argues, “When people talk about racial disparities in police use of force, they’re usually not asking, Is a black American stopped by police treated the same as a white American in the same circumstances? . . . They’re saying that black Americans are more likely to get stopped by police, which makes them more likely to get killed.”

One thing is clear: until we confront the terror that black folk have faced in this country from the time they first breathed American air, they will continue to die at the hands of cops whose whiteness is far more important in explaining their behavior than the dangerous circumstances they face and the impossible choices they confront.

Dyson sums it up when he says, “We do not hate you, white America. We hate that you terrorize us and then lie about it and then make us feel crazy for having to explain to you how crazy it makes us feel.”

R.E.S.P.O.N.S.I.V.E.

As we prepare to part, I offer you a few practical suggestions about what you as individuals can do to make things better:

- Reparation: Make reparation. If affirmative action is a hard sell, then reparations, the notion that the descendants of enslaved Africans should receive from the society that exploited them some form of compensation, is beyond the pale. There are all sorts of ways to make reparation work at the local and individual level. You can hire black folk at your office and pay them slightly better than you would ordinarily pay them. You can pay the black person who cuts your grass double what you might ordinarily pay. Or you can give a deserving black student in your neighborhood, or one you run across in the course of your work, scholarship help.

- Educate yourselves about black life and culture. Racial literacy is as necessary as it is undervalued. Start with James Baldwin, the most ruthlessly honest analyst of white innocence yet to pick up a pen. Read books about slavery that prove it was far more varied and complicated than once believed. Of course the classics must not be neglected, from Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk to Ralph Ellison’s novel Invisible Man, which wrestles with the perennial black problem of not being seen by the white world.

- School your white brothers and sisters, your cousins and uncles, your loved ones and friends, and all who will listen to you, about the white elephant in the room—white privilege. You must be an ambassador of truth to your own tribes, just like the writers Peggy McIntosh, Tim Wise (author of White Like Me and Between Barack and a Hard Place), David Roediger, Mab Segrest, Theodore Allen, and Joe Feagin. Whites must understand that they benefit from white privilege in order to realize how white privilege creates the space for black oppression.” As someone once said, “if one stays silent” then one is “actually helping racial injustice persist.”

- Participate in protests, rallies, local community meetings, and the like. Your participation makes a huge difference. When we gather to express grief, outrage, and dissent, your presence sends the signal that this is not “just a black thing.” It is, instead, an American thing.

- Oppose how black folk are routinely made the cultural other. There is a need to close the distance between the white self and the black other. In your own lives, at your own jobs, in your own communities—and in your own minds—you must see and root out the notion of “other.” You must constantly ask yourselves how you are thinking of, and responding to, the black folk you encounter in ordinary venues.

- New black friends: Not knowing black folk intimately exacerbates the distance between the white self and the black other. One solution is new black friends. It is distressing that so few of you have more than a token black friend, maybe two. Every open-minded white person should set out immediately to find and make friends with black folk who share their interests. The more black folk you know, the less likely you are to stereotype us. The less you stereotype us, the less likely you are to fear us. The less you fear us, the less likely you are to want to hurt us, or to accept our hurt as the price of your safekeeping. The safer you feel, the safer we’ll be.

- Speak up against the injustice that black folk face.

We need to hear your voices ring out against our suffering loud and clear.

- Immigrants: One of the issues about which you might speak, especially in your own circles, is the distinction between the immigrant and black American experiences.

- Visit black folk in schools, jails, and churches, reaching far beyond your circles. Become a mentor and offer career advice to older kids. Offer a word of encouragement to younger kids, too, especially through school counselors who know that black kids must see folk being what they one day wish to become—engineers, lawyers, architects, construction workers, and, yes, firefighters and cops.

- Empathy: All of this should lead you to empathy. It sounds simple, but its benefits are profound. Whiteness must shed its posture of competence, its will to omniscience, its belief in its goodness and purity, and then walk a mile or two in the boots of blackness. Empathy must be cultivated. The practice of empathy means taking a moment to imagine how you might behave if you were in our positions.

Dyson ends his sermon, saying, “We cannot allow hopelessness to steal our joyful triumph before we work hard enough to achieve it. We will not surrender because blackness is a gift that has blessed the world beyond compare.”