Click here to return to Blog Post Intro

The Purpose of the Creed

We tend to think that the purpose of a creed is to summarize all the content of Christian doctrine. But in fact, creeds were composed in order to bolster particular points of doctrine that were under attack—which is precisely the reason why there is so much in the Apostles’ Creed about Jesus and so little about the Holy Spirit.

The original purpose of most ancient creeds was to affirm faith in the Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—and to holster believers against those views that at the time seemed the greatest threats to Christian faith-views the church saw as contradicting some of the essential points of Christian faith. On the other hand, the Apostles’ Creed was composed when Christianity was trying to define its own identity in the midst of a society where all sorts of religions vied for people’s allegiance.

The Universal Use of the Apostles’ Creed

Suffice it to say that the Nicene Creed, although less familiar among Western Christians, is more widely accepted than the Apostles’ Creed. In the West, the Apostles’ Creed tended to eclipse the Nicene, at first primarily because of its simplicity.

The Apostles’ Creed focuses on the life of Jesus, following a chronological order that can be learned fairly easily: “born … suffered … was crucified, dead, and buried … descended … rose … ascended … is seated … will come.” By the middle of the fifth century, some people recited it twice it day as a reminder of their faith and perhaps even as a talisman against evil in general.

The Creed as a Personal Statement of Faith

At this point, it would be helpful to think of the Creed not so much as a personal statement of faith but rather as a statement of what it is that makes the church the church, and of our allegiance to the essence of the gospel and therefore to the church that proclaims it.

Look at the Pledge of Allegiance. People recite it at various times as a sign of patriotism, as an indication that they truly stand for the flag and with “the Republic for which it stands.” Yet when you stop to think about it, there are statements in that pledge that many who recite it would personally question—or at least interpret in their own particular way. To declare, for instance, that the nation is “indivisible” is to forget the horrors of the Civil War—or perhaps to remember them so vividly that they must he avoided at all costs. It is also to ignore the many racial, political, social. and economic divisions within the country and to ignore the way many exploit and foster such divisions for personal gain. And many who affirm that this indivisible nation lives “with liberty and justice for all” would question that there is indeed equal justice for all.

The pledge is not so much a description of what each citizen as an individual believes as it is a statement of the way the nation sees itself—the way it sees itself, partly in actual fact, and partly as an ideal. It is not so much my statement of faith as it is a statement of the faith of the church through the centuries-a statement that shapes the identity of the church, much as the Pledge of Allegiance shapes the identity of the nation.

I Believe in God the Father Almighty

Various Levels of Belief

Sometimes when we introduce a sentence by saying “I believe,” what we mean is that we are absolutely convinced of something—in some cases even to the point of risking our lives for its sake. But there is still another, deeper level at which one may say, “I believe in….” At this level, belief is close to trust.

What the Creed means is that we trust God, that we are willing to stake our lives on God, just as a child jumping off a ledge stakes her life on her father.

Believing In

When we declare, “I believe in God,” we are not saying only that we believe that God exists. Instead, we trust God for our lives, and also that it is in this God that we live and believe, that this God is both the foundation and the context of all our belief.

God as Father in the Teachings of Jesus

When Jesus referred to God as “my Father,” He was speaking mostly to relatively poor fishermen and peasants who lived in a social framework where a father was responsible for providing food and shelter, as well as loving care, to his children. His hearers could readily understand when He spoke to them of God as a father watching over his children, or as a father whose child asks for bread or for an egg.

The Creed in Its Context

In traditional Roman society, the figure of a father was not first of all a loving figure but rather a powerful one. The father of the family—the pateilumilias—ruled over it as a master, and was often a distant figure.

The Ruler of All

The very next word in the Creed is the word we now translate as “almighty.”

To say that God is pantokrator means first and foremost that God is the ruler of all. It is not, as we tend to think today, a statement about God’s power to do any and all things.

In Rome—particularly to one whose relationship with the paterfamilias was rather distant, as was probably the case with most Christians in the city—the declaration of belief in “God the Father Almighty” would not immediately bring to mind images of love and care, but rather images of power and authority.

God as Father Today

When we today recite the Apostles’ Creed, we interpret its very first words as an affirmation of God’s loving closeness to us. This is as it should be, for our God is indeed loving and close to us as a parent is supposed to be, and we do well in affirming and proclaiming this faith and this experience.

Belief in God

The Creed is not ultimately about what I believe: It is rather about the One in whom I believe: “God the Father Almighty.”

Maker of Heaven and Earth

A Later Addition

The words “Maker of heaven and earth” were added very early, and from that point all versions of what eventually became the Apostles’ Creed include them. Why? Probably for two reasons. The first reason was simply that most other creeds included a similar phrase.

The second reason is much more interesting and tells us much about the purpose of this particular clause. As we saw in the previous chapter, the Greek word now translated as ”almighty” is pantokrator, which literally means ”all ruling.” It therefore refers not only to the power of God in abstract hut also to the activity of God in all things.

Christianity had come to Rome from the Greek-speaking eastern portion of the Empire, and therefore most of its converts were people with those connections. The old Roman creed was translated into Latin, and in that translation, the Greek puntokrator (all-ruling) became onmilpotens (omnipotent).

The statement is an affirmation of God’s power, yet not of God’s power in general or in abstract but rather of God’s power vis-a-vis the created order.

Creator of Heaven and Earth

God’s power extends over all things. The phrase “heaven and earth” is another way of saying “everything.” The Nicene Creed explains it further by declaring that God is “Maker of heaven and earth, of all that is, seen and unseen.”

For many in our society, all that is important is material. Blinded by the brilliance of modern technology and by the ease of life it offers, they live as if all that mattered were the material.

Beyond all our discoveries—important and valuable as they may be—there always remains the mystery of mysteries, the God whose creative action is not exhausted by the world we see, but goes far beyond it, to what we cannot even imagine.

Creation and Science

The doctrine of creation is not about how God made the world; it is about this world and its inescapable dependence on God. Such a doctrine can never be proved or disproved by scientific research or analysis.

Creation and Nature

In summary, the doctrine of creation is not primarily about God but about the world.

“I believe in God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth.” And because I believe, I must love and respect this entire creation of which I am part, and in which God has placed me to carry out God’s purpose.

And in Jesus Christ His Only Son Our Lord

And in…

Three times in the Creed we affirm belief “in”: in the Father, in Jesus Christ, and in the Holy Spirit. The reason for this is the original connection of the Creed with baptism, which resulted in the Creed having the same Trinitarian structure as the baptismal formula, “in the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.”

Trinitarian doctrine affirms that the Father is God, that the Son is God, and that the Spirit is God; yet it also affirms that God is one.

Brazilian theologian Leonardo Boff has expressed it as follows, “God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit in reciprocal communion. They coexist from all eternity; none is before or after, or superior or inferior, to the other. Each Person enwraps the others; all permeate one another and live in one another.”

Our primary stance before the Trinity must not be to try to solve the mystery but rather to imitate the love!

Jesus Christ His Only Son Our Lord

“Jesus” is a name, and “Christ” is an adjective or a past participle meaning “anointed.” In fact, Clurisioc is the Greek equivalent of the Hebrew Messiah, which means “anointed.”

When calling Jesus “the Christ”—the Anointed One or Messiah—the early church was affirming both its continuity with Israel and its conviction that the hope of Israel had been fulfilled in Jesus.

His Only Son

For the first Christians reciting the Creed, it was equally important to make clear that Jesus is the Son of the God who is “Father Almighty. Maker of heaven and earth.”

Our Lord

The title of “Lord” (Kviios) was claimed by Emperor Domitian late in the first century. It meant that he was the supreme ruler and that no one could challenge or even rival his authority. Thus, when Christians dared call Jesus “our Lord,” they were uttering subversive and perhaps even seditious statements. They were claiming that there was another Lord besides—and even above—the emperor.

Our Lord?

When the early Christians declared, “I believe in … Jesus Christ … our Lord,” they were not making an innocuous statement. Nor are we. We are saying that our ultimate commitment is not to family, not to nation, not to church, but to Him. We are rejecting every absolute nationalism. We are rejecting any other unconditional allegiance.

Who Was Conceived by the Holy Spirit, Born of the Virgin Mary

A Common Misunderstanding

The purpose of these words is not to explain Jesus’ biological origin. It is rather to make two central affirmations about him: first, that his birth was something special: second, that his birth was real.

A Special Birth

For an agricultural people such as ancient Israel, the fertility of land, flocks, and people was of primary importance. If the harvest failed, or if the flock did not reproduce, there was famine. If a family had no sons to support it when the older generation was unable to continue working, the result was poverty and even starvation. Furthermore, if a couple failed to reproduce, this was usually seen as the woman’s fault. As a result, for a woman not to be able to conceive was considered a serious flaw and even a curse. This is why there are in the Bible so many stories of rivalries among wives and concubines, each trying to outdo the others in fertility, and often the barren one feeling inadequate.

We tend to think that the purpose of a creed is to summarize all the content of Christian doctrine. But in fact, creeds were composed in order to bolster particular points of doctrine that were under attack-which is precisely the reason why there is so much in the Apostles’ Creed about Jesus and so little about the Holy Spirit.

The theme of the barren women who conceive then has theological significance. They conceive as a sign that the children born of their pregnancies are not merely the result of natural forces, but are conceived and horn because of a specific act of God, so that God’s purposes may be fulfilled.

Luke makes it clear that just as Jesus is the culmination of the hope of Israel, Mary is the culmination of the theme of the barren woman who conceived by divine intervention. The song he puts on the lips of Mary, the Magnificat (1:47-55), is patterned after the song of Hannah (1 Samuel 2), another barren woman who conceives and hears a child with a specific purpose in God’s plans: Samuel.

A Real Birth

North African theologian Tertullian wrote, “Marcion, in order that he might deny the flesh of Christ, denied also His nativity; or else he denied His flesh in order that he might deny His nativity because, of course, he was afraid that His nativity and His flesh bore mutual testimony to each other’s reality, since there is no nativity without flesh, and no flesh without nativity…”

Note that the virgin’s conception serves to prove, not the divinity of Jesus as we might surmise, but rather his humanity.

Later Developments

The theme of the virgin birth became the object of much pious speculation that now centered on Mary more than on Jesus. Mary’s virginity in itself, rather than the one who was born of her, became the center of attention. Eventually this would lead to the claim that Mary herself was conceived without sin, that she was assumed directly into heaven, and even that she is with Jesus.

A birth is it sign of powerlessness, for the newly born is totally dependent on others, and the Creed affirms that Jesus underwent it. Over against this, all the speculation making the birth of Jesus clean and unreal plays into the hands of Marcion and his views, and denies the full humanity of Jesus, which the Creed is trying to safeguard.

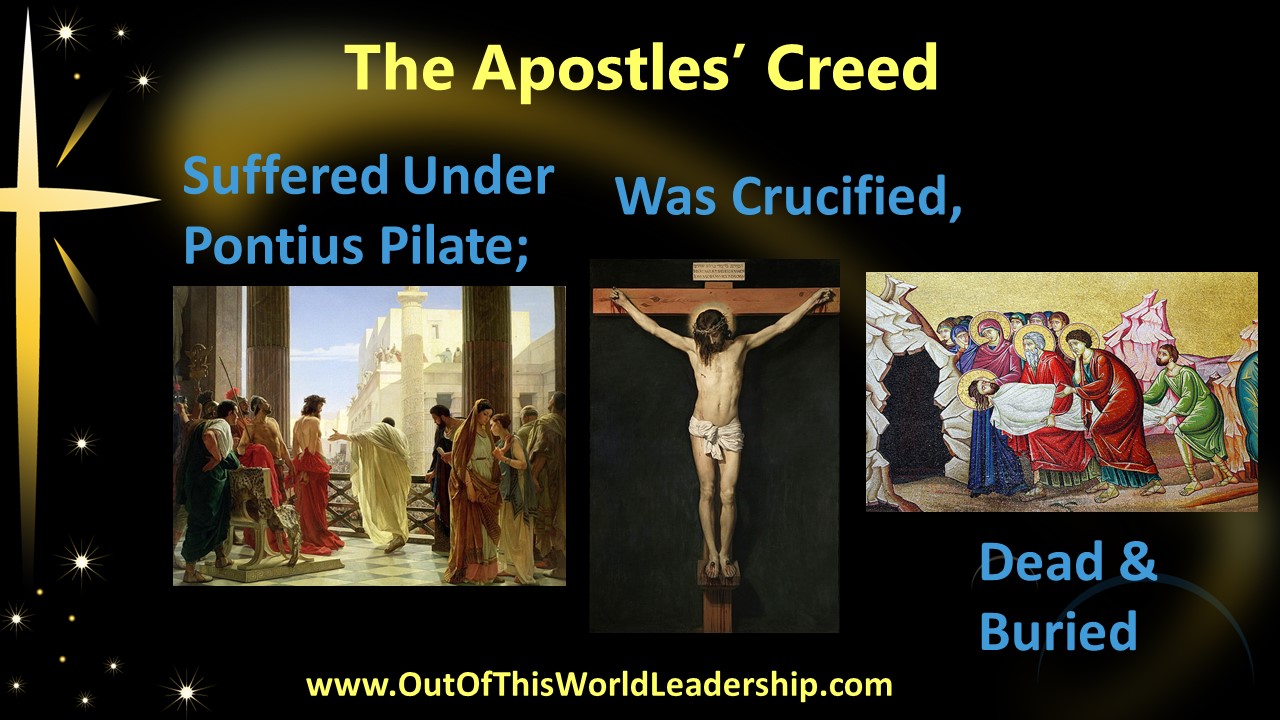

Suffered under Pontius Pilate, Was Crucified, Dead, and Buried

Why Pontius Pilate?

The name of Pontius Pilate does not appear in the Creed in order to lay blame, but simply as a date.

Now the Creed is about to state faith in a divine being who died and was brought back to life. This sounds very much like many of the surrounding religions of fertility. Various fertility gods die and rise again every year. Jesus Christ died and rose again only once, but this once is good enough for all the ages.

Was Crucified

For Christians in the Roman Empire the “scandal” was much worse than that. The cross of Jesus was not unique. On the contrary, crucifixion was the common way in which the Romans punished the worst criminals. It was a prolonged, agonizing death. But even more than painful, crucifixion was humiliating.

Once the person died, the body was often left hanging there, to be eaten by birds and eventually to break into pieces, with dogs and other scavengers picking up the bones. Although the body of Jesus was taken off the cross out of respect for a Jewish religious festival, His crucifixion was no less humiliating than any other.

What the Creed actually affirms is that the Lord died like a common criminal under Roman law.

Suffered … Crucified, Dead, and Buried

Christians insisted on the reality of the incarnation of God in a true, full, human being.

The reason why the Creed stresses the suffering, death, and burial of Jesus is to counteract the various theories circulating at the time, to the effect that Jesus did not really suffer and did not really die, for His body was heavenly and incorruptible—or, in the view of some, His body was not even real. Again, the Creed is not attempting to summarize all of Christian doctrine.

Some Reflections for Today

Many conservatives act as if prayer in schools, the teaching of creationism, and the banning of gay marriage would show that our faith is still at the center of our culture. They are convinced that, as Christians, they should first of all obey the law of the land and then condemn any who do not obey it, such as illegal immigrants.

They are convinced that society as it exists is generally good and quite compatible with Christian faith. But the Creed, and the experience of early Christians expressed in it, tells us otherwise. The one in whom we believe is a convicted criminal, not a respected religious leader. His followers should not expect to be particularly respected, and they should not expect society to support their faith. What happened to Jesus Christ under Pontius Pilate continues happening to his most faithful followers in every age and in any society.

He Descended to the Dead

A Slight Disagreement

If you visit different churches and recite the Creed with them, you will note that most of them—Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, Reformed—include the statement that “he descended to the dead” or “he descended into hell,” while some, particularly those of the Wesleyan tradition, do not.

John Wesley, being a patristic scholar, knew that it was not included in most creeds until a relatively late date—the fourth century in one particular case, but generally the sixth to the eighth centuries.

The Meaning of the Descent

The parallelism will continue as we move along the Creed, where we shall find that the one who descended is also the one who has ascended and is exalted, as Paul declares in the rest of his Hymn.

The descent into hell is the final affirmation of the real death of Jesus. It was a traditional Jewish belief that the souls of the dead went to a place below the earth. According to the Pharisees, they were there to await the final resurrection.

It was thought that Jesus descended into the place of the dead in order to preach to those who lived before Jesus and who were imprisoned in the place of the dead awaiting the presence and preaching of Jesus to them. This notion appears in First Peter, where we read that Christ “was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit, in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison, who in former times did not obey, when God waited patiently in the days of Noah” (1 Peter 3:18-20).

Another meaning traditionally attributed to the descent of Jesus into hell has to do with his victory over the powers of evil. In this view, the saving work of Jesus consists primarily in defeating those powers and thus undoing their hold on humankind. Early Christians referred to the work of Christ as having “killed death.” Thus, we find many early Christian writers referring to the work of Christ as a liberation from the powers of evil and as the beginning of the new humanity free from those powers.

On the Third Day, He Rose Again

He Is Risen!

What is expressed in these few words is the very crux of the Christian faith.

Paralleling Paul’s hymn in Philippians, we now cone to the point where Paul declares, “Therefore God also highly exalted him and gave him the name that is above every name, so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bend. in heaven and on earth and under the earth” (Philippians 2:9-10).

He rose again from the dead: Christ is risen, indeed. The center of what the Creed says about Jesus is the resurrection.

The Third Day

Counting from late Friday afternoon to early Sunday morning, we can best come up with thirty-six hours—and thirty-six hours is not even two days! Why then did people insist that Christ had risen on the third day! The explanation is simple. At that time people counted days, and years, much like vacation clubs and cruises count days today. If you go on an “eight-day cruise,” you leave late on Monday and return early next Monday. In fact, you have had only six full days and part of two; but the company advertising the cruise counts part days as whole days. This was the customary way of counting time in the ancient world.

According to this way of reckoning, Jesus was in the tomb three days—part of Friday, all of Saturday, and part of Sunday. Victory and Liberation!

Jesus Christ is not only the victim of Good Friday; he is also the victor of Easter Sunday!

The Third Day Is the First

The experience of that third day—the first day of the week—was so powerful that Christians began to meet every week on that day in order to celebrate it (Acts 20:7).

In contrast to what became common in the Middle Ages, the service of Communion was a joyful service, focusing on the resurrected One rather than only on the crucified One.

The Third Day Is Also the Eighth!

According to an ancient Jewish tradition, one day the apparently endless cycle of week after week was to come to an end. One day, after the Sabbath, instead of another first day of the week, an “eighth day” would dawn. Then would all of God’s promises he fulfilled. Then the kingdom of God would come and God’s shalom would prevail.

One of the most ancient prayers for the celebration of Communion says: As He Ascended into Heaven, Is Seated at the Right Hand of the Father

Not Just a Footnote

His ascension is almost like an epilogue in a novel, where we are told what happened to the various characters after the action ended! But the ascension is part of the story. It is an essential part of the story.

Easter Is Not Quite Over

We celebrate Easter every year. because we follow the cycle of the Christian year. But what we celebrate at Easter happened only once and continues to this day. The Lord who rose on that first Easter Sunday is still alive! What we celebrate at Easter is not the cyclical rebirth of nature, but the birth of a new reality, the dawn of the “eighth day,” the continuous joy that our Lord lives!

Nor Is the Incarnation Over

As Paul puts it, “Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have died” (1 Cor. 15:20). In other words, in His resurrection He is the first among many, and He continues being human, as we too will forever continue being human.

Is Seated at the Right Hand of the Father

To sit “at” the right hand of another is to have the place of highest honor. This goes back to the time when warriors carried a shield in their left hand and an offensive weapon—a sword, lance, or mace-in their right. This made them particularly vulnerable to attack from the right, and therefore every chieftain or king placed his most trusted warrior at his right. As a result, the custom evolved of having the most honored adviser of a king sit at the right of the throne. Similar customs continue to this day, when in many cultures it is customary to seat the guest of honor at the right hand of the host or hostess. To “sit at the right hand” is therefore a sign of great favor, of shared authority.

In brief, the ascension is about the victory of Jesus. It leads us hack to the text from Ephesians: that Jesus “when He ascended on high, He made captivity itself a captive” (Eph. 4:8).

And Will Come Again to Judge the Living and the Dead

A God of Justice

There are sermons depicting the Old Testament deity as an angry God, and Jesus as the soothing, forgiving, loving one. This is simply not true.

Perhaps what we need to do is to reconsider our concepts of both love and justice. In its most common usage both in our courts of law and in Our daily conversation, “justice” has to do primarily with punishing evildoers. In our daily conversation. we equate justice with someone “getting what’s coming to them.”

But justice is much more than that. Justice is when everything is in its proper place. (Note the relationship between “justice” and “adjust.” Adjusting things to their proper place, size, and function is a sort of justice.) Justice is when no one oppresses another, when all show mutual respect, when life and freedom and peace are affirmed.

Love, on the other hand, is not simply allowing others to do as they please. Love is truly concerned over the actions and the being of the beloved.

He Will Come

It is important to remember that the one who will come is the one whom we already know—the one who for our sake was horn, suffered, and was crucified, dead and buried, and rose again on the third day.

The judgment of God is a dreadful thing and much to he feared. But ultimately it is in that judgment that love will prevail. In judgment, God says “No” to our actions, to our efforts, to our very way of being, in order to say “Yes” to our true being and to bring it to fruition.

I Believe in the Holy Spirit

We Are Not Alone

It would be a very sad state for Christians were we limited to what we have said in the Creed to this point. The last clauses on the section about Jesus end with words of absence: “He ascended into heaven, is seated at the right hand of the Father, and will come.”

The promise of Jesus not to leave His disciples orphaned is fulfilled on the day of Pentecost. Jesus had told them that the “Advocate, the Holy Spirit,” would come to them, that this Advocate would be with them forever, and that thanks to this Advocate they would he in Jesus and Jesus in them-and they would even see Jesus!

The word that our Bibles translate as “Advocate” is parakletos. It is for this reason that, particularly in hymns, the Holy Spirit is called the “Paraclete.” This Greek word literally means “called to be by” … or “called to stand to the side of …” In the courts, a “paraclete” would he an advocate, a defender, but in tines of sorrow the paraclete would he one mourning with the bereaved. Thus, in today’s usage, a paraclete would he something like a “faithful companion,” a “comforter”—as the King James Version translates the word—or a “sponsor” or “supporter.”

The Spirit and Faith in Jesus

Paul declares that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except by the Holy Spirit” (1 Cor. 12:3).

Power for All: The Holy Spirit

The Spirit is God. The Spirit is powerful. The Spirit is not a plaything, just as a live wire is not a plaything. The Spirit is not there for us to manipulate or to seek to control or to use to our advantage. We try such things at our own peril. The Spirit is holy-and this to the utmost degree.

This Holy One is called “Spirit.” The word for “spirit,” both in Greek and in Hebrew, actually means “wind.” The presence of the wind is known by its power, by its sound. Sometimes we experience the wind as a gentle breeze and sometimes as a frightening storm. They are both the same wind, which chooses from what direction and with what force to blow.

The Holy Catholic Church, the Communion of Saints

Under the Heading of the Spirit

The holy church and communion of the holy—as with all holiness—is derived from the Holy Spirit.

The church is an essential part of the Creed because it is in it that we experience faith. The Creed affirms belief in the church not in the sense that the church is the object of our faith, but rather in the sense that it is within the church, in the context of the church and as members of it, that we believe.

The Holy Church

Along these lines, think of the phrase “Holy Land.” It is the land of Peter and Mary and James and Mary Magdalene, the land where Jesus walked, the land where he shed his tears and his blood. All of this does not make it particularly pure—on the contrary, it makes its constant history of war and hatred even more tragic. But it does make it holy.

We call it holy for the same reasons we call the land holy: This is the community of Peter and Mary and Janes and Mary Magdalene. This is the community in which martyrs have testified with their blood, in which missionaries have gone to distant lands for the sake of their faith, in which devout believers have devoted all their energies to the support and defense of the defenseless. This is the community in which millions upon millions—a “multitude that no one could count” (Rev. 7:9)—have found support in times of grief, and faith in times of anguish.

But above all, the church is holy because of the presence of the Holy Spirit in it.

The Holy Catholic Church

The word “catholic” does not appear in the earliest form of the Apostles’ Creed. It appears first in several creeds in the Greek-speaking branch of the church—particularly the Nicene Creed—and apparently from them made its way into the Apostles’ Creed at some point toward the end of the fourth century.

The word “catholic” actually means “according to the whole,” so that what makes the church catholic is not its presence everywhere, but rather the fact that people from everywhere are part of it and contribute to it.

Thus, when in the Creed we refer to “the holy catholic church,” we are not referring to a particular denomination. Quite the contrary, we are affirming the existence of the church even in the midst of our various theologies, traditions, and polities, and affirming our membership in that church.

The Communion of Saints

Its most obvious meaning would he something like “the fellowship of believers,” in which case it is little more than an explanation of “the holy catholic church.”

Comunio may mean fellowship, but it also means sharing. When we affirm “the communion of saints” we are affirming: (1) our fellowship with believers of all times and places; (2) our readiness to share with others who are in need; (3) that our sharing includes “holy things”—

in other words, that the “holy things” do not belong to some of us in particular, but to all of us as it whole.

But what about us today?

What do we mean when we recite these words in the Creed? We are certainly referring to the fellowship among believers, both present and absent. We probably are declaring that it is our sharing in “holy things” that makes us a fellowship—that it is our common faith, our common baptism, the one bread of Communion, that makes us one body. Perhaps we are even declaring ourselves ready to share with others in that fellowship.

The Forgiveness of Sins

A Continuing Issue

To affirm “the forgiveness of sins” is to affirm that we ourselves have been forgiven. Coming immediately after “the holy catholic church” and “the communion of saints,” it means that those of us who recite these words are part of the church because we are forgiven. But then, to affirm the forgiveness of sin is to affirm also the forgiveness of the sins of others.

Regarding the Lord’s Prayer, Jesus said, “For if you forgive others their trespasses, your heavenly Father will also forgive you; but if you do not forgive others, neither will your Father forgive your trespasses” (Matthew 6:14-15).

We are the forgiven people of God. But now we who have been forgiven so much insist on being paid full measure for whatever others owe us. So we say, “He did not thank me after all I did for him. I shall never forgive him!” Or, “She said something about me that was not flattering, and not entirely true. I shall never forgive her!” How can we forget how much more we have been forgiven?

The Resurrection of the Body, and the Life Everlasting

Life Everlasting

The earliest forms of the Creed ended with the words now translated as “the resurrection of the body.” “The life everlasting” seems to have been added not as a separate clause or a statement about a different belief, but simply as a clarification of what was meant by “the resurrection of the body.”

Augustine explains that true life is life in God and that therefore only that life which is eternal—that is, life in the presence of the Eternal—is true life.

Eternal Life as God’s Gift

Early Christians found the pagan philosophers’ notion of the soul and its immortality to be helpful. Christians speak more and more of the immortality of the soul, and less and less of the resurrection of the body—to the point that many came to the conclusion that what Socrates taught and what the church declares on this matter are practically the same.

The Resurrection of the Body

Christians insisted on the resurrection of the body for two main reasons. The first of these was to underscore God’s active role in Christian hope. The second reason why Christians insisted on the resurrection of the body was the need to affirm the positive value of the material.

This theme was of such importance that the original versions of the Creed, both in Greek and in Latin, do not really say “the resurrection of the body,” as do our modern versions. They actually say “the resurrection of the flesh”. In most translations of the Creed into modern languages this has been changed in order to take into account what Paul says about the unknown nature of the resurrected body.

This is the place at which the doctrine of the resurrection of the body has practical implications for our everyday life: “to love our own physicality and the worldly environment appropriate to it.”

We affirm “the resurrection of the body and the life everlasting.” The life for which we hope is life in the body. The life we affirm is life in the body. And, as believers in this final resurrection and this life everlasting, we now live in love and respect for these bodies that are called to rise again on that joyful day!