Click here to return to Blog Post Intro

June 19, 1865—shortened to “Juneteenth”—was the day that enslaved African Americans in Texas were told that slavery had ended, two years after the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed, and just over two months after Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox.

Major General Gordon Granger, who was headquartered in Galveston, prepared General Order Number 3, announcing the end of legalized slavery in the state. Given the significance of the day, Texans have been in the forefront of trying to make Juneteenth a national holiday.

Unfortunately, Granger’s order did not end slavery in the country. That did not happen officially until December 1865, when the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified by the necessary number of states.

Since the civil war had been fought to preserve slavery, celebrating Juneteenth throughout the land is a fitting way to mark the end of that effort.

“This, Then, Is Texas“

Let’s start with the size of Texas. Until Alaska became a part of the United States in 1959, Texas was the largest state in the Union—268,580 square miles; larger than Kenya, almost three times the size of the United Kingdom.

As one observer put it, “exaggeration is often considered to be an endemic low-grade infection of most Texans.”

“Everything’s big in Texas,” making the place and the people who live there seem larger than life.

When you consider the image of a “Texan,” what comes to mind. Frankly, the image of Texas has a gender and a race: “Texas is a White man.” What that means for everyone who lives in Texas who is not a White man needs further exploration.

Through cowboy lore and Hollywood films, there are a number of popular understandings about Texas and the people who live there. West Texas is, stereotypically, the home of the Cowboy, riding the range, and the Rancher, owner of the land on which the Cowboy worked. The third figure—the Texas Oilman—of more recent vintage, had his origins in East Texas, but migrated, first to North Texas and then West.

The legendary oil strike in 1901 at Spindletop established Texas as an oil-producing behemoth. The Oilman soon challenged the Cowboy and the Rancher as the archetypical Texan.

When Texas was part of Mexico, the Mexican government continued to move toward ending slavery, while the Anglos and their supporters kept resisting. The matter was settled when Texans successfully rebelled against Mexico and set up the Republic of Texas in 1836. With this move, the right to enslave was secured, and White settlers poured into the new republic.

White Texans feared that their new country’s weakness—Mexico remained a potentially formidable foe—made it vulnerable to calls for the abolition of slavery, which began to grow in the 1830s. The solution, Anglo-Texans believed, was to become annexed to the United States. Indeed, that had been the goal of many Texians (supporters of the break from Mexico) from the start. This happened in 1845, followed by the acceptance of Texas as part of the Union.

There is no way to get around the fact that, whatever legitimate federalism-based issues were at play, slavery was a central reason Anglo-Texans wanted out of Mexico. Using unpaid labor to clear forests, plant crops, harvest them, and move them to market was the basis of their lives and wealth. The choice for slavery was deliberate, and that reality is hard to square with a desire to present a pristine and heroic origin story about the settlement of Texas. There is no way to do that without suggesting that the lives of African Americans, and their descendants in Texas, did not, and do not, matter.

No other state brings together so many disparate and defining characteristics all in one—a state that shares a border with a foreign nation, a state with a long history of disputes between Europeans and an indigenous population and between Anglo-Europeans and people of Spanish origin, a state that had existed as an independent nation, that had plantation-based slavery and legalized Jim Crow.

As painful as it may be, recognizing—though not dwelling on—tragedy and the role it plays in our individual lives, and in the life of a state or nation is a sign of maturity.

A Texas Town

Gordon-Reed was born and raised in Conroe, Texas. Montgomery County, of which Conroe was the county seat, was known for being particularly harsh for Black people. Just to mention the more publicized examples, in 1885, twenty years after the end of the Civil War, in the town of Montgomery, just seven miles from Conroe, Bennett Jackson, a young Black man, was lynched after being charged with breaking into a home and assaulting a White woman and her children.

The lynching sent a clear message not only to Blacks, but to Whites, telling them what they could do to Blacks without fear. This knowledge operated along a continuum, from lynching down to nonlethal displays of disrespect without consequence.

For many years, Blacks in Conroe and Livingston—all over the country, really—have had their stories written out of history. What is the morality that would say that the oppressors’ version of historical events should naturally take precedence over the knowledge of the oppressed?

As Gordon-Reed noted, “The law might say I could go to a school or into a store. But it could not ensure that I would be welcome when I came to these places. I had vivid examples of this all around. There was a store near the border between our neighborhood and a White neighborhood whose proprietor was extremely hostile to the Black people who came into his store… For the most part, however, I took it as a given that Black people and White people were, for reasons I didn’t understand, at odds with one another. Or more precisely, I had the impression that the root of the problem was that ‘they’ (meaning Whites) didn’t like us, and that is why we didn’t get along—in much the same way one might say ‘dogs don’t like cats, and that’s why they don’t get along.’”

Patriarchy, which is not only about the subjugation of women but about competition between males, is so central to history. White males had, since the days of slavery, arrogated to themselves the right to have access to all types of women in society, while strictly prohibiting Black males access to White women, on many occasions becoming murderous about that stricture.

Integration changed Black students over time. A good number of them soon discounted the notion that they were any different than their White counterparts. After all, Blacks and Whites were in school together. By all outward appearances things were “equal.”

There have now been, and are, Black principals of schools—something that would have been unthinkable in Gordon-Reed’s childhood.

Origin Stories: Africans in Texas

Black people first appeared in North America in 1619. The story of the “20. and odd negroes” that John Rolfe announced, in matter-of-fact fashion, to have arrived in Virginia that year is often taken as the beginning of what we might call “Black America”—from that twenty, to 4 million—by the time of Emancipation in 1865—to nearly 40 million today.

Consider the difference between the stories of Plymouth, Massachusetts, and those of Jamestown, Virginia. Plymouth Rock gives Americans a founding story about a valiant people leaving their homes to escape religious persecution, and founding a new society in the wilderness, with the aid of friendly Indigenous people, like Squanto of the Patuxet.

At the other end of the scale, we have the narrative of Jamestown, created more openly as an economic venture in 1607. It is difficult to wrest an uplifting story from the doings of English settlers who created the colony for no purpose other than making money or, at least, to make a living for themselves. Not long after their arrival, they started down a path that would make Virginia a full-fledged slave society, the largest and richest of the thirteen colonies.

As famous as the Pocahontas–John Smith narrative may be, the story of America is often portrayed as having started in Pilgrim/Puritan–influenced New England. There is also a version of this attitude about Plymouth versus Jamestown in the origin story of African Americans. Gordon-Reed recalled hearing in school, probably because she was in Texas, stray references to a man of African descent—a “Negro”—named Esteban (Estebanico), who was in what would become Texas during the time of Spanish exploration. Interestingly enough, he arrived in the area of the future Galveston, where General Granger would proclaim the end of slavery in Texas over three hundred years later.

Estebanico, who was wandering (actually) around Texas—eventually across Texas—in the 1520s with the famous Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, appeared as a singular figure. There was no mention of the other people of African descent—some enslaved, some not—who arrived with the Spanish when they came to the Americas.

As early as 1565, the Spanish established racially-based slavery on American soil in St. Augustine, Florida.

The English “won” the contest against the Spanish in North America—in Texas and in Florida. From the English perspective, what was the point of incorporating the story of Africans and Spanish people into the general narrative of American history or, more specifically, the history of African Americans?

So much of racism is about announcing, in various ways, the agreed-upon fictions about Black people that justify attempting to keep them in a subordinate status; like the inanity that children produced from the union of a Black person and a White person were sterile, like a mule, in either the first or a later generation.

The fiction that has African Americans naturally speaking in a particular way, or unable to learn a language, slyly promotes the notion that Blacks are somewhat less than human, in their inability to master a human trait: the capacity to engage in complex communication.

Estebanico was described as a “black Arab from Azamor,” on the coast of Morocco. A Muslim, he had been forced to convert to Christianity and sold away from his home to Spain. He came to the Americas with the man who enslaved him, Andrés Dortantes, one of the leaders of an expedition of three hundred people to Florida, and Cabeza de Vaca.

Cabeza de Vaca, who lived to produce a wildly popular memoir of the extraordinary adventure, wrote about Estebanico as having played a key role as the chief translator between the Spaniards and the Indigenous people because of his great talent for learning and speaking languages.

Learning that the Spanish explorers, and the Indigenous people they encountered and lived with at times, relied on Estebanico to help them speak with one another brings another dimension to our understandings about slavery and the people enslaved. Even more, knowing that some of the Black people who came to the Americas with the Spanish went off on their own to lead expeditions of conquest in Mexico, Central, and South America would have altered the framework for viewing people of African descent in the New World.

Africans were all over the world, doing different things, having all kinds of experiences. Blackness does not equal inherent incapacity and natural limitation.

Estebanico and the Spanish-speaking Blacks of St. Augustine should be seen as a part of the origin story of African Americans. The origin story of Africans in North America is much richer and more complicated than the story of twenty Africans arriving in Jamestown in 1619.

People of the Past and the Present

White Texans have a story of how they came to live in and dominate the space, having “won” the territory by force, which rightly creates at least some degree of unease in a society in which the maxim “might makes right” is ostensibly rejected, and used to critique people who believe that force alone justifies outcomes, the story of conquest had to be leavened with examples of cooperation and, even, intermixture between the contending forces in the state.

Frankly, that the people who were doing the forcing were also the people who had held Black people in slavery deepened Gordon-Reed’s sympathy that there should have been an affinity between Blacks and Indigenous people in those times. There is a connection between Whites’ enslavement of Blacks and Whites’ forcing Indians off the land.

Land taken from Native peoples in Texas was then cleared by enslaved people, who were then put to work planting, tending, and harvesting crops.

It would be years before Gordon-Reed learned that the so-called Five Civilized Tribes—Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—had enslaved Black people, that some Native people held (and hold) the same racist attitude toward Black people that many Whites do. There was no “natural” alliance.

Indians and African Americans and, actually different Indians among themselves, should have recognized that they faced a common foe. But that is from the racial thinking of our times, which had largely been imposed by Europeans—creating people called “white” and categories of people who were “nonwhite” for purposes of deciding what rights people had and how they could be treated or mistreated.

After removing them from their land, preventing them from becoming a threat, Americans often claimed to admire the special virtues of Native peoples, who were supposed to possess a unique spirit. They named towns after them, states, later sports franchises.

Whites policed one another on racial matters, like Gordon-Reed’s White classmates who were friendly at school but acted differently when they saw each other out of that context, when they were with their families or other friends. This policing went on in the White community, as White friends could know the right thing to do—even want to do it—but could not bring themselves to do it because they feared losing the love, esteem, and support of their community. It was never just a matter of individual feelings or weaknesses, but the problem was structural.

Native peoples are now being asked to come to grips with their relationship to African Americans, the descendants of people whom they enslaved, and with whom, in some cases, they share a bloodline. The American story is, indeed, endlessly complicated.

Remember the Alamo

With those famous words, W. E. B. Du Bois, in his masterpiece The Souls of Black Folk, identifies the central dilemma facing Black people in the United States—that, to a great degree, “Blackness” and “Americanness” have been cast in opposition to one another, a predicament created by the details of history and the desires of others.

The idea of violence as a solution to a problem has plagued humankind from the beginning. People all over the world have employed violence to move situations from one point to another. But there is no question that violence has been at the heart of the Texas story, and violence has been foregrounded in the origin stories of Texas, in ways it is not in other states.

The Texians were ready for independence. Even before the fall of the Alamo, delegates had met at Washington-on-the-Brazos and drafted a Texas Declaration of Independence that is essentially a knockoff of Jefferson’s American Declaration—pronouncements, followed by a list of grievances. What the Texas Declaration very pointedly does not take from Thomas Jefferson are any words about “self-evident” truth that “all men are created equal.” There was no place for such language in a battle in which race and culture were central. General Provisions of the Constitution, also drafted in this intense period, make concerns about controlling people of color, protecting slavery, and managing the new republic’s racial future very clear.

In the new republic, only Whites were welcome. From Section 9, “All persons of color who were slaves for life previous to their emigration to Texas, and who are now held in bondage, shall remain in the like state of servitude.” It went on to say, “No free person of African descent, either in whole or in part, shall be permitted to reside permanently in the republic without the consent of congress.”

Slavery was to be a permanent state for Blacks.

There is often great hesitancy about, and impatience with, discussing race when talking about the American past. The obvious difficulty with those kinds of complaints is that people in the past—in the overall American context and in the specific context of Texas—talked a lot about, and did a lot about, race. It isn’t some newly discovered fad topic. Race is right there in the documents—official and personal.

Consider how history tells the story of the heroes of the Alamo. Idealizing an individual one doesn’t know personally usually involves taking the things one admires and making them embody the individual as a whole. When a historian comes along and says, “Oh, you do know that William Barret Travis came to Texas one step ahead of the law to avoid being jailed for his debts, abandoning his wife and two small children in the process?” That can be discomforting.

Gordon-Reed explains, “I will freely admit, as realistic about figures in the past as I am, that it disappointed me when I learned of Travis’s misdeeds, even though I had no great expectations of him. It was an irrational response, born of the residue of early training about Travis’s actions at a particular moment in his life and the life of the state I lived in and, probably, because he was played by Laurence Harvey in the movie The Alamo.”

And then there is the whole business of Jim Bowie, with his shady deals and slave trading. The answer to this, of course, is that we should refrain from idealizing human beings.

On Juneteenth

On June 19, 1865, as relayed at the beginning of this volume, Gordon Granger, a general in the Army of the United States of America, arrived in Galveston from his post in Louisiana to take command of all the troops in the American army in Texas. The Civil War had been over since April, when the Army of Northern Virginia, headed by General Robert E. Lee, surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant, commanding general of the Army of the United States. Confederate soldiers in Texas, nevertheless, continued to fight on into May.

Granger’s job was to get to the state, geographically the largest in the Union, impose some degree of order, and announce that all enslaved people were free.

General Order No. 3 had a powerful effect in Texas. The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

This Order was based on the Emancipation Proclamation that President Abraham Lincoln, who had been assassinated the previous April, had issued on New Year’s Day, 1863.

While the holiday Juneteenth has grown to be an integral part of life in Texas, celebrated now by Blacks and Whites—and appears on its way to becoming a national holiday—Whites in Texas were incensed by what had transpired, so much so that some reacted violently to Blacks’ displays of joy at emancipation.

All over the South, but in Texas particularly, Whites unleashed a torrent of violence against the freed men and women—and sometimes, the whites who supported them—that lasted for years. The language of General Order No. 3 not only announced the end of slavery; it used a concept familiar to Americans from the very beginning, though as we know, it was not carried forward. After stating “all slaves are free,” the order continues: “This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.” Language about equality echoed the words of the American Declaration of Independence, “all men are created equal.”

Confederates had explicitly rejected the concept of equality announced in the Declaration, as the vice president of the Confederacy, Alexander Stephens, made clear in March 1861 in his infamous “Cornerstone Speech.” The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution.

The Framer’s compromise over slavery had left matters unclear enough to be the source of “agitating questions.” That uncertainty was caused, in part, by the way some members of the founding generation viewed the institution of slavery and people of African descent.

That is the basis upon which Texas and other members of the Confederacy had formulated their society. Even before the war, Texas had made this a part of its creed in its own Declaration of Independence that formed the Texas Republic. While it copied the form of the American Declaration, as noted, it left out the language of equality.

Announcing the end of slavery would have been shocking enough. Stating that the former enslaved would now live in Texas on an equal plane of humanity with whites was on a different order of magnitude of shocking. Had the Order said, “Slavery is over. And former slaves will now become the equivalent of peons on the land of whites, with severely diminished to nonexistent legal, social, and political rights”—the state eventually imposed in Texas and throughout the South—the reaction may have been different. But this Order portended much more than that.

Seeing that Black people could exist outside of legal slavery put the lie to the idea that Blacks were born to be slaves. Making life as hard as possible for free African Americans, impairing their movement and economic prospects—even if that meant the state would forgo the economic benefits of talented people who wanted to work—was designed to prove that Blacks could not operate outside of slavery.

Two months after General Order No. 3 was created, the federal agency set up to help the newly freed people in the wake of the change in their status, the Freedmen’s Bureau, opened its Texas branch in Galveston. Conceived as part of the United States Army, General Oliver Howard was made commissioner of the Bureau. Howard, the Maine career soldier, would go on to found and serve as the first president of Howard University.

General Howard, heading a new bureau that was underfunded and poorly staffed, found Texas the most difficult of all the regions under the Bureau’s jurisdiction, its White citizens the most resistant to efforts to effect changes in the position of Blacks in the state. Why would White Texans be more obstreperous than other White southerners? It has been suggested that this was because, unlike other Southern states, Texas had not been defeated militarily. They had won the last battle of the Civil War. That the state had been its own Republic, within the living memory of many Texans, also set them apart from the other Confederates. The very thing that has been seen as a source of strength and pride for latter-day Texans, may have fueled a stubbornness that prevented the state from moving ahead at this crucial moment.

In 1901, a hurricane wiped out Galveston Island, killing as many as 12,000 people and is still considered the worst natural disaster in the history of the United States. The city was determined to rebuild quickly after the destruction. It did so, in part, by inviting large numbers of immigrants to come to work in the city. In sum, Galveston was, for Texas, progressive and cosmopolitan.

If the promise of Juneteenth lived anywhere in Texas, it was in Galveston. That sense of promise spread across the state. Black Texans were determined, despite the early intimidating anger of Whites, to celebrate what was initially called Emancipation Day. Most of the first celebrations were in churches, in keeping with the culture of a generally religious people.

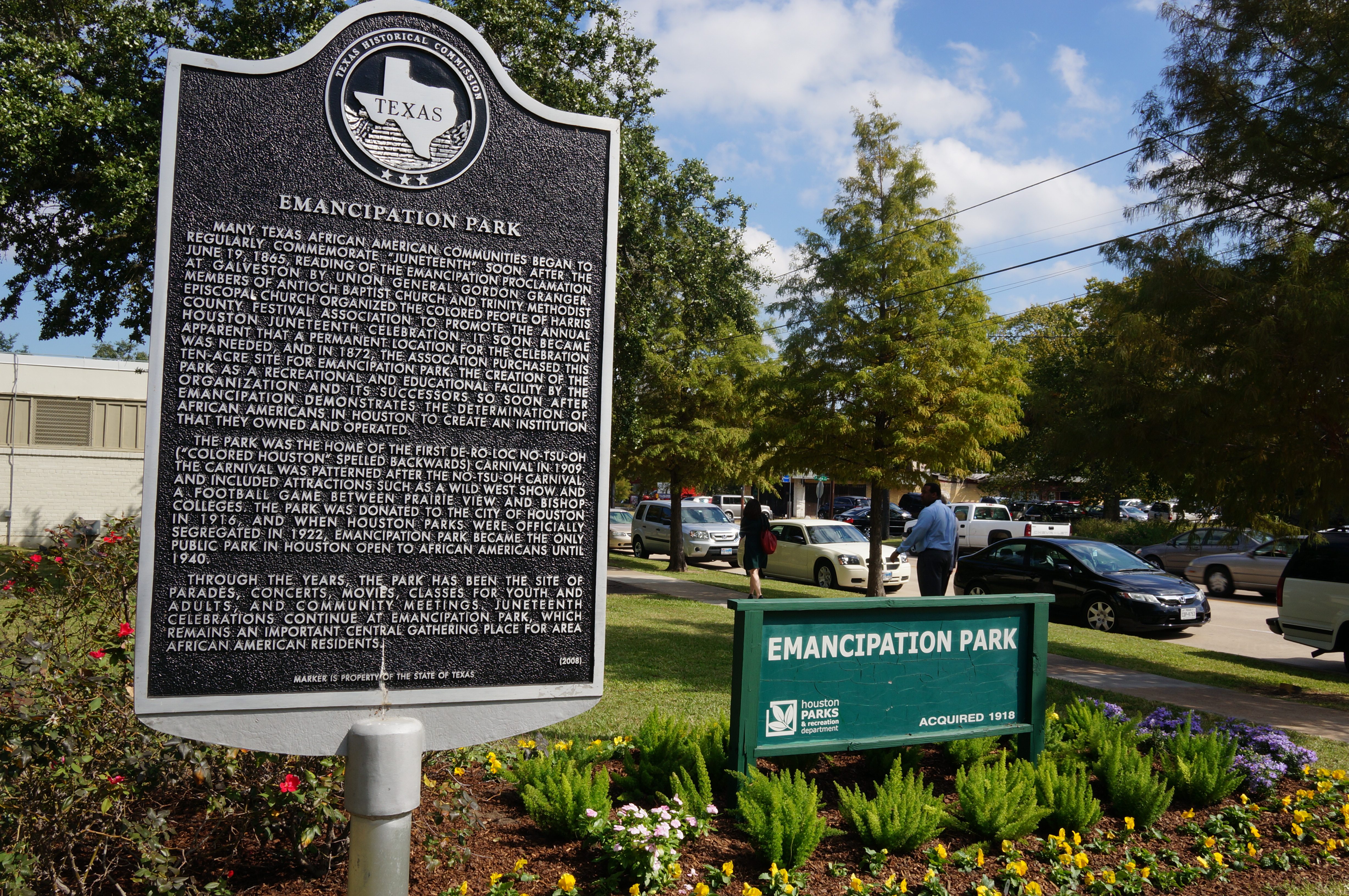

Later, in larger towns, the celebrations migrated to public spaces, though some sort of religious observance might be included in the program. In 1872, in Houston, four Black men, Richard Allen, Richard Brock, Elias Dibble, and Jack Yates, pooled their resources and raised money to buy land in the city for the express purpose of celebrating the holiday, creating Emancipation Park, one of the oldest parks in Texas. It was later taken over by the City of Houston, and in those days of segregation, it was a park for Blacks.

Juneteenth is the first part of a one-two summer punch: June 19 followed closely by July 4—the holiday expressly for Black Texans and the other holiday for all Americans. Whites generally do not celebrate Juneteenth. But everyone celebrates the Fourth.

Some Blacks have a tradition of celebrating July 5, as a protest to remind people that the ideals of July 4 had not been realized.

Conclusion

Thomas Jefferson wrote in his Notes that an enslaved person (which, because of the racially based nature of slavery in the country, meant a Black person) could not love the country in which he or she lived. He reasoned, “How could they love a country that did not love them, as evidenced by the way the country had treated them?” Therefore, Blacks would be happier in some other place, their own country, free from the racial strife that he couldn’t see as anything other than inevitable.

In his last will and testament, freeing his five slaves, Jefferson petitioned the legislature of Virginia to allow them to remain in the state. He had to do this because, according to Virginia law, an enslaved person who did not get permission to remain in Virginia within a year after emancipation, could be sold back into slavery. When explaining why these men should be allowed to stay, Jefferson said, because Virginia was where “their families and connections” were. At the level of theorizing about nations and countries, it was easy to speak in the abstract—the slave, the country. When dealing with the lives of actual, known people that mattered to him, the focus became sharp and clear.

Gordon-Reed recalls, “When asked, as I have been very often, to explain what I love about Texas, given all that I know of what has happened there—and is still happening there—the best response I can give is that this is where my first family and connections were.”

About the difficulties of Texas: Love does not require taking an uncritical stance toward the object of one’s affections. In truth, it often requires the opposite. We can’t be of real service to the hopes we have for places—and people, ourselves included—without a clear-eyed assessment of their (and our) strengths and weaknesses. That often demands a willingness to be critical, sometimes deeply so. How that is done matters, of course. Striking the right balance can be exceedingly hard. Gordon-Reed concludes, “I hope I’ve achieved the proper equilibrium.”