Click here to return to Blog Post Intro

Childhood in White

What Wasn’t Said

Lessons Irving’s mother couldn’t teach her.

Stereotypes are not so much incorrect as incomplete.

English people coming to America was part of a larger historical pattern of white Europeans invading countries, exploiting resources, and “civilizing” people they considered to be savages, all in an entangled quest to dominate through Christianity and capitalism.

Without ever once mentioning the words “race” or “skin color,” generations passed along the belief that the two were connected to inherent human difference.

What stereotypes about people of another race do you remember hearing and believing as a child? Were you ever encouraged to question stereotypes?

Family Values

The making of a belief system.

Irving explains that she identified 100 percent as a New England WASP, with parents and an extended family who bore all the trappings of the social elite and an extensive network of like-looking and like-minded family and friends with whom to preserve an Anglicized, Yankee culture. Like many New England Yankee families, her family’s roots went back to the Mayflower and other early boatloads of English settlers.

Frugality must have been a carryover from the Puritan days, as were restrained emotions and extreme modesty about the body. These three values weighed heavily in Irving’s understanding of the world.

Her extended family lived by the motto “Work Hard; Play Hard.”

From a young age, Irving internalized the idea that accomplishment for anyone was simply a matter of intention and hard work.

Tales of Mayflower settlers and other early American ancestors suggested that America provided a kind of neutral template on which anyone could design the life they chose.

Displays of anger showed poor rearing; pride was gauche; sadness, anger, jealousy, and fear were just plain pitiful—all worthy of being shunned with silver-clinking-on-china silence or a swift change of subject. A “good attitude” was highly valued and rewarded.

“Last but not least,” Irving’s father used to smile in recognition of her efforts. Her status as youngest child created a lifelong sensitivity to people—especially children—who feel “less-than” in any way, shape, or form.

What values and admonitions did you learn in your family? Think about education, work, lifestyle, money, expression of emotions, and so forth. Try making a list of ten principles, values, and unspoken beliefs.

Race Versus Class

Everyone wants to know: Which one is the real issue?

Irving recognizes that she is not only white but a white Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP), from a family with plenty of socio-economic advantage.

Understanding whiteness, regardless of class, is key to understanding racism.

You might find yourself thinking, “Wait a minute—this is about class, not race.” People often debate the entangled relationship between race and class. “Which one is the real issue?” people ask. “Is it race or class?”

Any cycle that traps someone in a state of perpetual disadvantage is the real issue for the person experiencing it. Unlike poverty, skin color is visible and fixed, forever and always.

An element of class in Irving’s story is the persistent sense of needing to “help” and “fix.” These characteristics are considered by many to be trademarks of the dominant class.

Every white person can awaken to the impact the ideology and practice of whiteness has on our brothers and sisters of color.

Optimism

The downside of perpetually looking on the bright side.

Trying to protect children by providing a worry-free childhood is a privilege of the dominant class—a white privilege. Many parents of color teach their children to keep their hands in plain sight if a police officer is near and to avoid white neighborhoods in order to avoid being questioned simply for being there. In the same way Irving was trained to make herself visible and seek opportunity, many children of color are trained to stay under the radar and avoid suspicion.

Within the Walls

The exclusive world of thriving people raising thriving children.

For much of Irving’s life, the word “exclusive” brought warm, fuzzy feelings. An exclusive resort, exclusive club, or exclusive school meant top-notch quality. But doesn’t “exclusive” actually mean people are being excluded? How did it ever become okay to exclude someone?

It’s impossible to fully quantify the accumulated and compounded advantages that came simply from living day in and day out with a small group of people connected to each other and to untold resources. Problems are private.

Perhaps this is why the civil rights movement seemed so removed from Irving’s life until two decades after landmark protests and policy changes shook the country.

The big houses, the private educations, the clubs, the optimism—Irving recognizes that she believed all of these were earned through nothing other than hard work and high ethics. For most of her life the idea of unearned privileges remained unheard of—an unfamiliar concept from an unknown American reality.

How connected to or disconnected from the larger world was your family, your school, your town? How much did you understand about conflict and struggle in your world or beyond?

Midlife Wake-up Calls

From Confusion to Shock

The course that changed the course of Irving’s life.

As Irving put it, “I saw difference as just difference, not better or worse. I was nice and kind to people of all races and cultures. I believed every person could make it in America, if just given the opportunity.”

Racism is, and always has been, the way America has sorted and ranked its people in a bitterly divisive, humanity-robbing system.

The late historian Ronald Takaki referred to the history taught in American schools as “The Master Narrative,” the version of history told by Americans of Anglo descent.

Think about what you did not study. Did you learn about Lincoln’s views on enslaved black people? Anti-immigration laws of the nineteenth century? America’s laws regarding who could and could not gain citizenship? The Native Americans who had once lived on your town’s or school’s land?

The G.I. Bill

Discovering the meaning of unearned privilege.

An elderly black couple, Mr. and Mrs. Burnett, spoke about the day half a century earlier that they’d excitedly driven out to a New York suburb, Levittown, to look for a home. Mr. Burnett, a returning GI, and his wife drove through a neighborhood and toured a house, imagining themselves living there. They were convinced: this was the lifestyle they wanted. When Mr. Burnett approached the realtor, expressing his interest and inquiring about the purchase procedure, the realtor sheepishly told him he couldn’t sell to Negroes. “It’s not me,” he explained. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) had warned the town’s developers that even one or two nonwhite families could topple the kind of values necessary to profit from their enterprise. The Burnetts were crushed.

Reality is that while the American dream fell into the laps of millions of Americans, making the GI Bill the great equalizer for the range of white ethnicities in the melting pot, Americans of color, including the one million black GIs who’d risked their lives in the war, were largely excluded. The same GI Bill that had given white families a socioeconomic rocket boost had left people of color out to dry. In the end, a mere 4 percent of black GIs were able to access the bill’s offer of free education.

On the housing front, it got worse. A set of policies created by the FHA, and implemented by lenders and realtors, mapped out neighborhoods according to the skin color of residents. This national housing appraisal system, commonly referred to as “redlining,” deemed skin color as much a valuation indicator as a building’s condition. Neighborhoods inhabited by blacks or other people of color were outlined in red, the color in the legend next to the word “Hazardous” (investment).

Home values in black neighborhoods plummeted, while those in white-only areas rose, with an FHA and lending-institution color-coded map spelling out exactly which was which.

As houses were bought and sold according to skin color and loans were rated and made based on skin color, black folks were left to make do with the remains of city housing, under assault by another federal effort, the Urban Renewal Program. Dubbed by James Baldwin as the “Negro Removal Program.”

This critical juncture in American history created a housing footprint that fossilized our communities into skin-color-coded haves and have-nots, reaffirming segregation and provoking increased mistrust between the races. Between 1934 and 1962 the federal government underwrote $120 billion in new housing, less than 2 percent of which went to people of color.

From the perspective of Americans excluded from this massive leg-up policy, the GI Bill is one of the best examples of affirmative action for white people.

Irving reflects, “If my childhood of racially organized comfort and opportunity had made me feel like the master of my own destiny, full of confidence, and certain of a bright future, what did this imply about people on the flip side of the coin—people who’d been shut out of a world of comfort and opportunity?”

Racial Categories

The day Irving learned race is more of a social construct than a biological certainty.

No science supports the idea that genetic makeup follows the neat racial lines white people have created. No science links race to intrinsic traits such as intelligence or musical or physical abilities. In March 1960, America’s four-hundred-year-old skin color sorting and ranking scheme landed Irving in the white skin category—the dominant, top-of-the-heap group.

The biggest problem with America’s idea of racial categories is that they’re not just categories: they’ve been used to imply a hierarchy born of nature. Regardless of how racial categories came into being, Americans have been cast in racial roles that have the power to become self-fulfilling, self-perpetuating prophecies.

White Superiority

How white people decided white people were the best people of all.

Race is a “social construct” and a “human invention.”

The first attempt to categorize humans by skin color seems to have been made by a white Frenchman named François Bernier, who in the mid-1600s traveled throughout the Middle East in his role as physician for a Persian emperor. In his view, the world’s people sorted into four categories: white, yellow, brown, and black. By publishing his observations, Bernier put the idea of racial categories on the radar of his white European readership.

By the 1720s pale skin had become a beauty ideal for white people, making its way into European art and literature. During these same years, white European colonization of Asia, Africa, and the Americas was gathering speed, fueling ideas of white dominance and superiority.

Entangled in all of this were white European missionaries bringing Christianity to far-flung parts of the world. Core to their work was the belief that the white, Christian way was the superior way and that “taming the heathens” in order to save their souls required a full-on conversion to Christianity.

Whiteness, it turns out, is but a pigment of the imagination.

The Melting Pot

Thinking for the first time about who could and could not melt into the pot.

“White ethnics” refers to light-skinned people immigrating to America from non-Anglo countries like Ireland, Italy, Russia, and Germany. Between 1820 and 1920, 17.3 million people immigrated to the United States from these countries.

Irving points out that even her O’Doyle ancestors dropped the O’. For those who had escaped a homeland in pursuit of survival or the American dream, assimilation—the idea of adopting the dominant culture’s norms—became a norm unto itself, one utterly unattainable unless one is white.

What Irving didn’t know was that while millions of white immigrants, including her own Irish ancestors, did in fact overcome initial desperate circumstances and ethnic discrimination, the very same rights and resources that allowed their socioeconomic mobility were denied to darker-skinned immigrants—and, of course, to the indigenous people who had been here before everyone else and to the African Americans brought here against their will in America’s earliest days.

Indian schoolchildren had no control over the internalized beliefs held by the white people awaiting them in the outside world. Unlike the millions of white ethnics who were able to “melt” into the pot, indigenous children could not shed the physical attributes that marked them as different and inferior. No longer Indian, unable to be white, these young adults ended up belonging nowhere.

For much of American history, people who couldn’t pass for white lacked not only social acceptance but also access to citizenship, the legal status needed to reap the full rewards of the American dream. Individuals without citizenship can’t vote, run for public office, own land, or work in the higher-paying jobs of America’s economic machine. Whiteness didn’t just earn normalcy or a sense of belonging; whiteness was nothing short of a lifeline. In the 175 years between the Naturalization Act of 1790 and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, American courts used a vague definition of skin tone as a primary qualifier for who could and could not be a citizen.

Through most of US history, white skin has acted as a free pass, while dark skin has impeded freedoms and rights.

Even whites cannot all assimilate because we do not all share one single heritage, one look, or even one common American experience. Isn’t the more intelligent choice to create a culture built around difference?

In the film Race: The Power of an Illusion, sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva comments: “[The] melting pot never included people of color. Blacks, Chinese, and Puerto Ricans could not melt into the pot. They could be used as wood to produce the fire for the pot, but they could not be used as material to be melted into the pot.”

Headwinds and Tailwinds

How Irving finally came to understand systemic racism.

There are three basic elements of systemic racism:

- Skin color symbolism: using skin color to imagine innate levels of intelligence, athleticism, aggression, and so forth in oneself and others

- Favoritism: the idea that one is the best

- Power: the ability to make decisions for and/or distribute resources to people

Skin color symbolism + favoritism + power = systemic racism

A black woman at one of Irving’s workshops offered this perspective to those struggling with the concept: “All racial groups have problems with people in other racial groups,” she said. “White folks have not cornered the market on that. The difference between white folks and everybody else is that they have the power to turn those feelings into policy, law, and practice. White folks run everything in this country.”

In American society, racism acts as a barrier, a divider, allowing white people to benefit from the system in ways people of color do not.

The racially divisive belief barrier shows up in all American institutions: in medical policy, in emergency rooms, in education reform, in classrooms, in corporate hiring policies, in workplaces, in lending policies, in banks, in urban planning, on city streets, in policing practices, in courtrooms, in federal policies, in state policies, and in municipal policies.

Systemic racism touches every aspect of every American life, and skin color determines how.

As Jim Hightower said about President George W. Bush, and one could say just as easily about me, “[He] was born on third base [but] he thought he had hit a triple.” Unacceptable is the counterpart to that: the kid who hits and hits and still gets nowhere, ultimately coming to believe in his own inferiority.

At this point, the only thing needed for racism to continue is for good people to do nothing.

“Why Didn’t I Wake Up Sooner?”

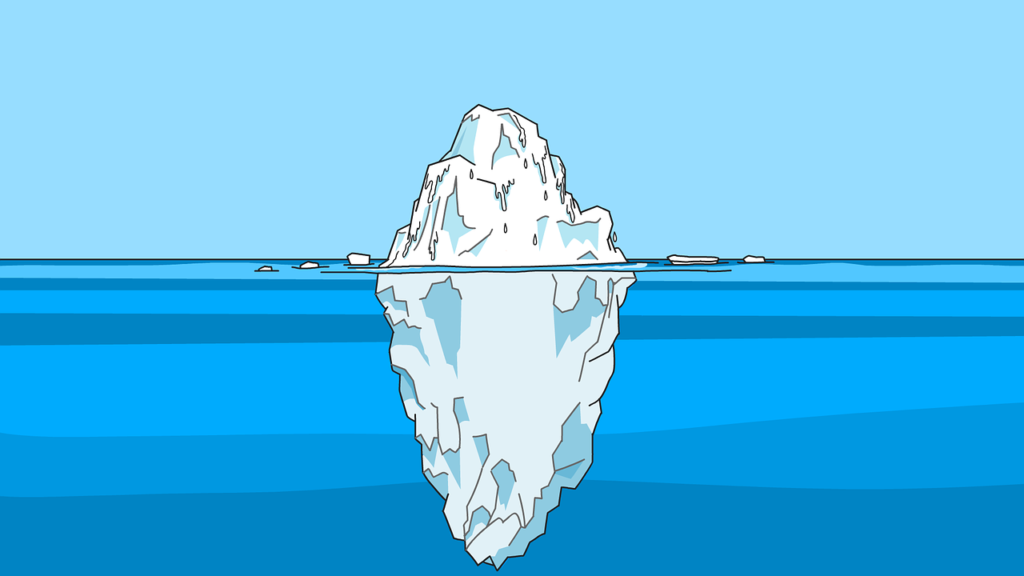

Icebergs

Seeing is believing, or is it the other way ’round?

Culture is to a group what personality is to an individual. It’s a collective character that describes a set of beliefs and behaviors that identify the group. Though individuals in the group vary, these common beliefs and behaviors hold the group together.

Sociologist Kenneth Cushner explains culture by dividing an iceberg into two parts: the 10 percent above the waterline and the 90 percent below.

Above the waterline are the things we can see and hear: spoken language, body language, clothing, material possessions, job titles, foods, and traditions, for instance. Below the waterline and invisible to the eye are the beliefs and values one adopts because they are the norms of one’s culture.

One of the basic beliefs Irving adopted early in life was the idea that in America people failed or succeeded based on individual skill and effort. She could see that the white folks were living in the best houses and running America’s institutions—government, schools, hospitals, banks, corporations, and media, so she assumed white people were in charge because they were more capable.

Ideas create outcomes that, if unexamined, reinforce old ideas—America’s oldest idea being that the white race rules. White folks don’t just control America’s institutions; they control the narrative. And the narrative controls just about everything else.

Invisibility

Out of sight, out of mind.

Working in lockstep with the iceberg phenomenon, in which we see what we already believe, is another phenomenon: inattentional blindness, also known as selective seeing.

Without any understanding of systemic racism’s ability to produce drastically different life experiences and outcomes along racial lines, Irving assumed her daily experience was basically universal. People were mostly friendly, she felt mostly safe, and those with authority encouraged and supported her. Making visible the privilege of white skin is key to racism’s undoing, and antiracists coast to coast are continually looking for new ways to help white people see the phenomenon as real and operating 24/7 in their own lives.

In her essay “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack,” Dr. Peggy McIntosh laid out the forty-six seemingly benign privileges she dislodged from her subconscious—“benign” because they don’t seem like big deal until their opposites, or the lack of privileges and the discrimination are considered.

Privilege is a strange thing in that you notice it least when you have it most. Consider that you’re never more grateful for the privilege of good health, for instance, than when you’re sick.

Irving explains, “As a white person, whether or not I know it, whether or not I admit it, I’ve got white privilege, an advantage that both is born of and has fed into white dominance. There’s an interesting circularity to this learning. The more I understand the privilege side of the equation, the more I understand the discrimination side, and vice versa.”

Discrimination and privilege are flip sides of the same coin.

It’s not enough to feel empathy toward people on the downside; white people must also see themselves on the upside to understand that discrimination results from privilege.

The way America’s lending and housing systems have partnered to create a segregated housing footprint plays a massive role in maintaining the alternate universe syndrome. Segregation enables avoidance, which enables denial, which creates the illusion that white privilege doesn’t exist.

Zap!

The discomfort of trying to cross racial lines.

The fact that the playing field is not level means that life experiences are not merely different, but unequal and unfair.

While friends and acquaintances of color bottled up accumulated racial pain, Irving notices that she maintained a degree of racial oblivion that made her a poor listener for their tender and charged words.

Irving considered all the times she’d casually introduced her children to adults of color using the grown-ups’ first names. She thought of the way she took the liberty of calling adults of color she didn’t know all that well by their first names and wondered what impact it might have had on them. Did her casual tone impart the authentic spirit she meant or an indication of disrespect? Using first versus last names meant something entirely different for Pamela from what it meant to Irving.

Then, Irving thought of the Golden Rule—the set-in-stone belief she’d been raised on, that one should always treat others the way you yourself would want to be treated. The limitations of this adage in the realm of race relations struck her like a thunderbolt.

Part of the power differential is that white people have the choice, the power, to ignore race and racism. Whites can choose not to have a single cross-racial relationship. Whites can choose not to talk about race. And whites can choose not to learn the beliefs, customs, traditions, and values of racial groups other than their own. Not so for people of color, who can’t escape knowing what life looks like in White Land.

White people are more likely to hire white people. White teachers are more likely to understand and gravitate to white students. White police are more likely to trust and support white citizens. White doctors are more likely to relate to and appropriately treat white patients. White bankers are more likely to make speedy, low-interest loans to people who look and act like them.

If the people with less power, in this case people of color, try to convey the way the dynamic disempowers them, they risk being seen as ungrateful, paranoid, weak, irrational, and unworthy.

One of Irving’s African American friends explained, “My mother trained us well. She told us, ‘This is where the good schools are, and if you want to make the most of it, you need to stay away from drugs.’ You know what else she told us? ‘White kids who do drugs go to college; black kids go to jail.’” She leaned closer and whispered, “That’s still happening today you know, more than ever.”

Cross-racial relationships are essential to racial healing.

The Whole Story

The effect of swallowing one-sided stories.

It’s no coincidence that the word “story” is contained in the word “history.” Either way, we’re talking about human-constructed narratives used to describe people, values, places, eras, and events. Stories are a primary way we connect to those around us and before us.

Irving pondered, “What if instead of a glorified history of family members connecting me to a glorified history of the United States, I’d learned a more balanced history in which humans and their endeavors are both imperfect and ever- changing? What if, at a young age, because of a more balanced narrative told through history classes, I could have tied the story about Lydia and the land grant to the harsh reality that there was no such thing as ‘free land’ to be given away, that land grants were parcels of land stolen from indigenous people who’d lived on them for tens of thousands of years? What if I could have learned how one person’s windfall can be another person’s downfall?”

The story of race is at the center of racism’s entanglement.

As long as the dominant culture holds fast to a story of white as right, the possibility of hearing other truths gets shut out, and the cycle continues: white folks experience people of color’s versions of events as incongruent and therefore inadmissible.

Logos & Stereotypes

The snap judgments that fueled Irving’s racial anxiety.

In his book Language in Thought and Action, Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa writes, “Animals struggle with each other for food or for leadership, but they do not, like human beings, struggle with each other for things that stand for food or leadership, such things as our paper symbols of wealth (money, bonds, titles), badges of rank to wear on our clothes, or low-number license plates.”

Snap judgments about people are not always about race. White people make them about other white people. Black people make them about other black people. Turning people into logos, symbolic of a neatly wrapped story, is not race-specific.

The word “slave” likely originated as “Slav,” the term used for captured white Slavonic people sold by other Europeans to Arabs as indentured servants during the eighth and ninth centuries.

Even in America, the earliest “slaves” came in a variety of skin colors, from a variety of countries, and worked in the capacity of indentured servants. Unlike white European indentured servants, African people were imported against their will, kept here against their will, and defined and treated as a separate and subhuman species.

Irving notes that she finds it easy to label people who aren’t white—he’s Hispanic, she’s black, they’re Asian—but until recently, she has not labeled white people. No matter how much she tries to stay open-minded and follow Dr. Martin Luther King’s advice to “not judge people by the color of their skin but by the content of their character,” Irving is am fighting against the tide of stored negative data.

Rethinking Key Concepts

Irving’s “Good People“

Irving asks, “How it was possible that I was both a ‘good person’ and utterly clueless?”

Learning the ways in which racial categories had been used to elevate the status of whites in relation to all other humans mitigated Irving’s sense of passive guilt. Guilt got crushed by culpability. Seeing herself in a system with people as opposed to a sympathetic observer on the sidelines changed Irving’s relationship to the problem. She understood then that it was possible to be both a good person and complicit in a corrupt system.

Color-Blind

Why saying “I don’t see race” is as racist as it gets.

In the same way cancer might not come up if you didn’t know anyone experiencing it, we didn’t understand that we were experiencing it. Racism simply was not on our radar.

In the film White Privilege 101: Getting In on the Conversation, which explores different racial groups’ understanding of white privilege, Irving watched a mirror image of her talking-about-race epiphany: a young black woman explained, “I couldn’t believe it when I found out white people don’t talk about race every day. I thought everybody talked about race every day. Not talk about it? How can you not talk about it?”

In his article “The Right Hand of Privilege,” Dr. Steven Jones explores invisible privilege by reminding readers of the myriad ways our society is set up for right-handed people. He asks readers, “How many of you, who are right-handed, wake up in the morning thinking ‘My people rule’?”

Color-blindness—a philosophy that denies the way lives play out differently along racial lines— actually maintains the very cycle of silence, ignorance, and denial that needs to be broken for racism to be dismantled.

Irving’s Good Luck

How she perpetuated racism by taking advantage of her “good luck.”

Among other things, socioeconomic privilege affords the freedom to explore, take risks, and find work you truly love—the kind that brings out your best.

Irving’s Robin Hood Syndrome

The audacity of thinking she knew what was good for “others.”

Irving felt complete shock that “inner-city” seemed to equate with “black.” Without an understanding of systemic racism, she couldn’t understand why, after all the years since slavery had ended, these kids’ families hadn’t made it out to the suburbs or into workplaces like her father’s. Irving concluded these inner-city black folks just needed more chances to see what opportunities existed.

She rarely went to inner-city neighborhoods, fearful of their reputations for violence and unfamiliar with the lay of the land. Not once did it occur to her that the reverse might hold true for the people who called those neighborhoods home and hers unfamiliar. The idea that Irving’s world might feel uncomfortable or even dangerous to someone else would have been inconceivable to her. Had someone tried to point out to her that she was part of a national pattern of white people deciding what people of color needed, and white people holding the purse strings, Irving guesses that she would have silently smiled while thinking, “How ungrateful.”

Unprepared for any potentially challenging conversation about racism, Irving’s comfort zone extended only as far as the general concept of “diversity.” She was decades away from grappling with its deeper components: invisible privilege, the Zap factor, missing narratives, and horribly misguided stereotypes.

Irving’s “Robin Hood era” ended with the sound of a deflating balloon, not the accolades and gratitude she’d anticipated. Neat and tidy endings, especially happy ones, are yet another luxury of the entitled.

Twenty-Five Years of Tossing & Turning

Children have taught me to confront unvarnished truth and unpleasant facts I’d often like to avoid. —Marian Wright Edelman

Straddling Two Worlds

Irving describes the “Winchester me, Cambridge me, and the man who helped me find the real me.”

Never once did it occur to Irving to ask herself, “What is white American culture? And why is it so different from other American cultures?”

Think of different groups of people in your life—your family, your friends, your coworkers, and so on. For each of these groups or contexts, think about whether you feel like an insider or outsider and how that status affects your desire to spend time with the group.

Irving asks, “Why do I always end up with white people?”

She moved to Cambridge for the diversity but ended up surrounded by white people.

In this multicultural city, Irving began to surround myself with friends who were a lot like her—white, American, thirty-something, middle-class to upper-middle-class, mostly of northern European heritage. Where was the variety she originally sought?

Two distinct groups of mothers formed at the playground, both white. Irving’s group was the private-college-educated women who’d grown up in a variety of US suburbs. The other consisted of women who had grown up in Cambridge, had gone to state colleges, and were now working part-time or odd-shift jobs. Irving’s group’s husbands worked all over the world in white-collar jobs. Most of the other groups’ husbands worked for the city of Cambridge or in blue-collar jobs. Though all were white, the division was unmistakable. So were the attitudes and behaviors attached to each.

Playground after playground offered up the same basic demographic: predominantly white, divided into the white-collar group and the blue-collar group.

Diversity Training

The harder Irving tried, the worse it got.

The word “articulate” is one of those words white people tend to use to describe a person of color who is able to string a sentence together—the implication being that this is a rare thing, an exception. For a racial group that has had to prove its intelligence over and over again, setting the bar this low is insulting.

“Do you have any advice for me?” Irving would ask people of color. She was years from learning just how weary people of color are of being in the position of having to educate white people. Irving hadn’t made the connection that this is one reason why white people becoming racially aware and coaching other white people to do the same is so important.

Irving got an email back in which she was reassured that this stuff was tricky but to try to remove the guilt piece—it would only interfere with progress—and to please stick with it.

Everyone is Different; Everyone Belongs

The power of inclusion.

When Irving asked white teachers how they explained the divergent outcomes according to skin color, some would just raise their eyebrows and not say much. Her interpretation of this was that they saw the gap as proof positive that black kids were inherently less able and willing—or perhaps just poorly raised. This theory never made sense to her.

Irving kept wondering, Why? Why? Why? Why all these patterns together, at once? Why is an entire population experiencing lower socioeconomic standards? Why aren’t black and Latino parents as involved as white parents? She was years from learning that the answer lay not just in looking at those who were not achieving but in examining the experiences of children like mine, the white kids who thrive. Now it seems obvious, but for most of her life Irving couldn’t see how much easier life is for most white people in America, and how that ease includes a level of comfort in taking one’s place as a leader—be it in a classroom or a boardroom.

Nor could she see how as white people assume leadership roles, their voices and actions can squeeze out those of their peers and colleagues of color, reestablishing a pattern in which white people appear more able. Like so much about racism, the cycle is self-perpetuating.

Consider Dr. Petner’s “Everyone Is Different; Everyone Belongs” philosophy. To reach its full potential, its believers must take into account not just variable abilities, but variable realities—realities that are very different according to racial identity.

Belonging

How Irving’s sense of belonging also allowed her to feel entitled.

A typical school’s parent body manifests an achievement gap of its own, an “involvement gap” one might say. Irving observed that a majority of kids of color came to and from school by bus, while many white kids were dropped off and picked up by parents, grandparents, or caregivers.

Eventually Irving settled on this self-congratulatory sentiment, “If they’re too busy to be here, I’m glad parents like me can be so there’s a parent presence at the school.”

All across America, white parents, disproportionately able to drop off and pick up their children, gain an edge in the community-bonding department. Socializing in the halls and on the playgrounds, white parents like me form a close-knit adult community. Without thinking about the repercussions of our actions, we deepen white bonds and strengthen the voice of the white parents.

White people, in general, grew up with a sense of belonging in America, while people of color did not. Saturating our culture is the ultimate message: “Belonging to Club America is primarily for white folks.”

In her book The Education of a White Parent, former Boston School Committee member Susan Naimark, a white woman, uses the term “entitlement gap” to describe the way white parents bring a host of assumptions and attitudes to a school community.

White parents think nothing of contacting their school principal and requesting (or even demanding) their child be placed in so-and-so’s class next year. They specify the teachers and peers they want as well as the teachers and peers they don’t want. It’s a common white practice in America’s public schools.

Irving’s white children ended up in the stronger cohort with the stronger teacher. Children of parents who felt less entitled ended up with the leftover teacher and the leftover students. Headwinds and tailwinds.

Studies have shown that parent involvement in their children’s schools improves student achievement.

“Everybody has a context—groups, neighborhoods, and organizations—in which they feel empowered, and everyone has a context where they feel ‘otherized,’” Naimark wrote. “And it’s not just about race. In India, I’m an ‘other’ because I’m an American. At Simmons [the all-women institution where she teaches MBA students] I feel a sense of belonging because I’m a professor and I’m a female. Depending on where you are, you can feel more or less empowered.”

Surviving Vs. Thriving

The psychic costs of racism.

We keep people down by lowering our expectations of them and then forcing them to live down to them. Consider the phrase “Go along to get along,” describing the kind of forced compliance that comes with oppression.

Powerlessness creates a state of fear, which puts people in survival mode. Who can be anything close to their best in this state? It’s what Andrea Stuart describes in her book Sugar in the Blood about slavery’s effects over generations as “psychological disfigurement.”

Living into Expectations

Witnessing the impact of racial legacy.

Consider the experience of a young black kid Irving met, who saw a pattern of behavior that included black kids going to the principal’s office and black family and friends going to jail. It would make all the sense in the world to see himself on a similar trajectory. Not yet aware of the mass incarceration system plaguing his community, Irving attempted to reassure him that crime was a choice, not a predestined path. Unprepared, confused, and upset, Irving felt ill-equipped and lost for any other words of wisdom or support.

Their two worlds barely resembled one another. Irving’s made her believe she belonged to a country where she could do anything she set my mind to; his reminded him every day that achieving in white-dominated institutions was for people who didn’t look like him.

Irving Recognizes She Is The Elephant

Finally realizing what she’d missed all along—and feeling like a fool.

By 2009, the year the Wheelock course finally opened her eyes, Irving had spent twenty-four years trying to “help” and “fix” others so that they could “fit in” without once considering my role in perpetuating the dominant culture that was shutting them out.

She knew there was an elephant in the room. She just didn’t know it was her.

How can racism possibly be dismantled until white people, lots and lots of white people, understand it as an unfair system, get in touch with the subtle stories and stereotypes that play in their heads, and see themselves not as good or bad but as players in the system? Until white people embrace the problem, the elephant in the room—and all the nasty tension and mistrust that goes with it—will endure.

Little did Irving know when she began the awakening process the degree to which she’d need to leave behind her culture of bravado, comfort, and polite conversation to open up and grow.

Leaving the Comfort Zone

Intent & Impact

Just because we don’t mean it to hurt doesn’t mean it doesn’t.

Everyone can cite examples of times when their intentions have been misunderstood or they’ve misunderstood another’s. Cultural difference combined with pent-up emotions can lead to complex and charged intent-versus-impact upsets.

Irving reports, “The hard thing to understand and acknowledge is how readily I slipped into a comfortable old role of the white person who feels entitled to express her opinion and offer advice. When I’d heard the black woman’s frustration, I also slipped right into my old white role of being a fixer and a comforter.”

Why was it so hard to allow the people in that room to feel and process their own emotions and ideas?

Facing up to the unintended impact she could unleash on people through sheer ignorance was painful. It humbled Irving and motivated her to become more of a learner and less of a knower. It taught her that efforts to defend her intent in the name of her “good person” status had no place in this world or in her efforts to learn and grow.

Irving continued, “I could walk away. I could retreat to my white world, where racism would be off my radar. But five of the people standing around me, and any person of color who has ever lived in America, must think about and deal with racism on a daily basis. For me to have walked away in this intensely uncomfortable moment would have been invoking my white privilege.”

Feelings & the Culture of Niceness

Freeing herself from the conflict-free world of WASP etiquette.

Irving’s parents—warm, funny, kind, and smart, so competent in so many ways—were utterly unprepared for one thing in life: navigating emotional conflict. Typical of their era, race, and class, they believed unpleasantries belonged under the rug, where, the hope must’ve been, the magic winds of time would blow them away.

Not every white family buys into the culture of niceness and shuts off their feelings.

For centuries, people have learned that in America’s classrooms, boardrooms, and public places, those who most often succeed are those who conform to the dominant culture prototype, which demands emotional restraint.

The admonition “If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all” served as a cultural signpost as Irving developed an acute sense of what not to say and what not to feel in order to remain valued.

She internalized this “Nice is good” norm so thoroughly that she came to loathe conflict and judge harshly those uncivilized enough to stir it.

Whom exactly does the culture of niceness serve? It likely serves the people for whom life is going well, the people in power. Speaking truth to power too often results in feelings of judgment and anger at the complainer.

Courageous Conversations

Learning to listen and speak across difference.

For people who fit the cultural norm—white, Christian, heterosexual, and so forth—the culture of niceness might be more palatable.

Isn’t this what “oppression” is? Pressing down and invalidating feelings and pressing down and invalidating people? The great irony is that while denying negative emotion and feedback might be an attempt to maintain individual or group control, it actually fuels anxiety and social unrest, states of being that then require more efforts to control. It’s the psychological equivalent of “Penny wise, pound foolish.”

The state of racism in America is a brewing, toxic stew. Allowing anger and mistrust to fester between groups of people promises a cycle of division in which each group can reaffirm its narrative about the other, keeping us in a self-destructive holding pattern.

White people must learn how to listen to the experiences of people of color for racial healing and justice to happen.

Getting Over Herself

The liberation of letting go of her self-image.

When Irving describes her efforts to understand how being white shaped her views and allowed her to perpetuate racism without knowing it, Irving sees shoulders relax, and often a smile.

Perception & Fear

The first time Irving saw herself as white—and scary.

Replacing oppression with equity is all people of color ask for.

Inner Work

Whenever a transition is called for, view it as your soul knocking at the door of your life, bearing more gifts for you to bring to the world. Change is a call from your soul to grow. —Sonia Choquette

Becoming Multicultural

Learning to navigate a complex world by using multiple approaches.

Creating a racially just world demands a reconsideration of the assimilation (“melting pot”) model long enforced in America.

Just as Irving sought for twenty-five years to bridge the racial divide by “helping” others, many people hope that “helping” or “including” or “celebrating” people from nondominant racial or other cultures is the goal of multiculturalism—that it’s all about the “other.”

Irving notes that in her experience, she could not begin to develop a multicultural sensibility until she first looked deep within herself to understand the ways in which the culture she’d lived in ended up living in her. Skipping over this critical step is what set her up to spend twenty-five years futilely trying to help and fix people so they could align with her personal sense of normal, good, and right.

There’s no rule that says we have to reject our own culture. But if we become aware of its beliefs, values, and practices, we can try to see it as one culture of many and expand our beliefs, values, and practices beyond it in the name of becoming a better global citizen. Learning to value other cultures’ ways demands a kind of psychic stretching that taps into our human potential. As we let go of believing in “one right way,” we can discover new ways to think about ourselves and the people and events around me.

Change requires flexibility, adaptability, open-mindedness, and resilience—qualities Irving is stretching herself to develop but that many people of color already have embedded in their subcultures.

If Only You’d Be More “Like Me”

After years of wanting to help and fix others, Irving learned she had her own work to do.

During all the years Irving tried to help and fix people of color, part of her subconscious expectation had been that people outside her culture should assimilate to her ways, see and do things the way she’d been taught was right and normal. Unlike in her marriage, however, where Irving and her husband felt free to tell each other how frustrated they were, in cross-racial relationships such freedom of expression often does not exist.

There’s a long and painful American history of people of color, when in the presence of white people, conforming to survive. The cost is staggering. The silencing of feedback from people of color can create a deadlock dynamic in which white people remain ignorant about their impact, while people of color accumulate frustration.

While slavery and Jim Crow laws provided white people tangible evidence of racism and clear-cut demands for its undoing, today’s racism lives hidden beneath the surface, in individual hearts and minds.

The Dominant White Culture

Irving was moving from not knowing what it was to feeling it in every recess of her being.

Irving’s cultural imprint bears all the hallmarks of the dominant white culture.

Since she’s always viewed herself as an individual, succeeding or failing on her own merit, the idea of white skin lumping her into a white culture felt foreign and offensive.

It’s not that she had never felt a part of a group; she just never felt part of a racial group.

Here’s a list of dominant white culture behaviors:

- Conflict avoidance

- Valuing formal education over life experience

- Right to comfort/entitlement

- Sense of urgency

- Competitiveness

- Emotional restraint

- Quick to judge

- Either /or thinking

- Belief in one right way

- Defensiveness

- Being status oriented

Boxes & Ladders

Getting in touch with her either/or thinking habit.

Either/or mindset, the part of Irving that makes it so effortless to stereotype people as either this type or that, either this race or that. Her either/or tendency interacts with a ranking habit, making people not just different but better or worse. She calls these partners in judgment “boxes and ladders.”

When Irving thinks about where she got the idea that intelligence and insight correlated to a certain type of person, it comes back to what wasn’t said. Though no one close to her bad-mouthed people outside of her culture, the constant praise for people, especially white men, within her culture made its mark.

The Rugged Individual

Learning to value both independence and interdependence.

Like many cultural messages, the idea that independence reflects strength while dependence results from weakness seeped into her psyche without anyone explicitly saying it.

Irving’s glorification of independence and individualism made her an easy target for the myth of meritocracy, and overshadowed what in her heart she knew to be true: the deep interconnectedness she longed for with family, friends, colleagues, and even strangers is core to human survival. Interdependence is our lifeblood.

There is tension between the tradition in American education of expecting children to work quietly and independently and the growing evidence that peer learning is in fact a more effective strategy. Encouraging students to reason together and explain their thinking to one other, it turns out, results in higher levels of comprehension and proficiency.

For children who come to the United States from Latin America, the idea of working independently goes against everything they’re taught at home. Likewise, studies have shown that African American students perform better in collaborative learning settings. Both of these cultures revolve around a collective orientation as opposed to an individual one.

Equality Starts with Equity

Adjusting an understanding of what’s fair.

“Fair means equal.” This attitude fits nicely with the myth of meritocracy.

Once Irving recognized the imbalance of resources and access historically given to white people, her ideas changed. Suddenly things like affirmative action and housing subsidies, which had once sounded like unfair programs that helped people she assumed simply weren’t helping themselves, made sense.

Equality means giving every student exactly the same thing to meet the same expectation. ‘Equity’ means both holding people of differing needs to a single expectation and giving them what they need to achieve it.” In other words, it’s a way to level the playing field.

It’s interesting to think about how acting in ways beyond the white culture facilitates the creation of racial equity. Consider replacing conflict avoidance with explicit conversation and conflict resolution.

One anti-racist activist worked with white communities to examine their degree of comfort and entitlement relative to communities of color. Instead of acting on a sense of urgency, he took the time necessary to include multiple perspectives, develop collaborations and consensus, and think about long-term impacts.

Which of the following special-by-race programs have benefited you in your life? How?

- White-only or white-dominated neighborhood

- White-only or white-dominated country club

- Other types of white-only or white-dominated social clubs

- Legacy at a private school

- Legacy at an institution of higher education

- Lending rates for white people

Bull in a China Shop

How habits that seem so innocuous can alienate people of color.

Until Irving became aware of how her internalized white ways of thinking and acting interfered with her best intentions to bridge the racial divide, she was like a bull in a china shop. What passed for normal in her white world had the potential to alienate people of color.

When Irving starts a workshop, she points out that when it comes to racism, everyone has something to teach and something to learn.

Consider this conversation with a well-meaning white woman. “You remember how you asked Henry right off the bat what he did for work?”

“That’s one of those things I’ve learned can drive people of color crazy. It’s the first question you ask in a white setting, right? ‘What do you do?’”

“For people of color, it can easily be felt as you questioning someone’s credentials. And frankly, most cultures around the world don’t rank what you do for work as a hot topic of conversation. This glorification of professional status is a white culture thing.”

There’s a tendency in the white culture to need to label someone, to identify them, before you can relate to them. Like when people say, “What are you?” meaning, “Are you Korean or Japanese or Chinese or what?” It really bothers people of color. For them it’s like, “Why do you need to know that? Can’t you just relate to me without needing to put me in a box?” So Irving always tries to stick with something she has in common with the person—like today, a good question might have been, “What workshop did you go to this morning?”

“So, what do you do for work?” felt as normal and polite as saying please and thank you, Irving now sees a clear connection to her boxes and ladders mindset.

Even the most seasoned white racial justice educators and activists will tell you that they still rely on those around them to point out the ways in which their white-grown perspective or behavior might be interfering with their best intentions. The key is to keep learning and always take feedback when it’s offered.

Outer Work

From Bystander to Ally

When it comes to racism, there’s no such thing as neutral.

Understanding her internalized tendencies as a white person was just a start for Irving. The ultimate goal is to interrupt, advocate, and educate without doing more harm than good—something she is in danger of doing every day.

As historian and activist Howard Zinn said, “You can’t be neutral on a moving train.”

Opportunities abound for white people to move out of the bystander role and into the ally role in an effort to prevent racism from getting fueled and refueled every day, across every sector, and in every state, city, and town.

Irving recognizes that there’s a critical role for her in dismantling racism. But here’s the catch: it’s trickier than one would think to take on the role of ally and not be, well, too white. She should not be in the role to take over, dominate, or be an expert. The role is not for her to swoop in and “fix.” The white ally role is a supporting one, not a leading one.

Irving will always have to check her privilege, her perceptions, and her behaviors as she tries to work in alliance with people of all colors in the struggle to interrupt, advocate, and educate.

Solidarity & Accountability

Sharing the burden of racism.

A man of color once signed a note to Irving, “In solidarity, James.”

The definition of “solidarity” includes descriptors such as “union,” “fellowship,” “common responsibilities and interests.” In a thesaurus she found the antonyms “enmity, hate, hatred, partiality, unhealthiness, unsoundness.”

In the film Mirrors of Privilege: Making Whiteness Visible, a black woman describes her feelings about friendships with white people. “For you, wanting to be my friend is like a simple stroll across the room. For me, it’s like crawling on my hands and knees across a room of broken glass.” Putting in extra effort in recognition of this inequity is something Irving is learning to do—which doesn’t mean it’s easy.

The long history of white people mistaking one black person for another is one of those unintended consequences of racism that deepens the divide. Mistaken identity has caused everything from a “Do my coworkers even know who I am?” feeling of invisibility among people of color to false accusations resulting in retaliation, incarceration, and death.

Vernā Myers, a black attorney, has worked since 1992 with white law firms that are scratching their heads about their lack of success in attracting and retaining lawyers of color. She’s learned how microaggressions on the part of white employees have driven away employees of color.

It can be as simple as not learning a co-worker’s name. Consider the person of color who responded, “Not want to have to learn his name? Are you kidding me? That’s what this is about? Man, we black folks have been learning everything about you for years! We know your TV shows; we know your hair products; we know your names; we know how you like to do things. We have to! Is it really that much to ask to meet us halfway?”

From Tolerance to Engagement

Why “tolerance” and “celebrating diversity” set the bar too low.

Vernā Myers puts it this way: “diversity is being invited to the party; inclusion is being asked to dance.”

An article written by Harvard Business School professors David Thomas and Robin Ely titled “Making Difference Matter: A New Paradigm for Managing Diversity” addresses the need for strategies beyond simply adding people of color to one’s team in order to bring in “insider information” or to speak to same-race clients. Thomas and Ely point out that members of groups outside of America’s dominant culture “bring different, important, and competitively relevant knowledge and perspective about how to actually do work—how to design processes, reach goals, frame tasks, create effective teams, communicate ideas, and lead.”

What if instead of “winner take all” in a world of haves and have nots, a society of thriving people expanded the pie for everyone?

Listening

Listening both to bear witness and to learn.

In the film White Privilege 101: Getting In on the Conversation, a black interviewee talks about how people tend to speak at each other, not to or with each other. At one point he says, “You know what we need? We need a listening revolution.”

Whether it’s individuals listening one-on-one, or events organized for the purpose of collective listening, allowing people to define their own realities is a critical component of creating equity.

Challenge yourself in the next conversation you’re part of to ask more questions than you typically would and refrain from offering your own opinion. Take note of where the conversation goes.

Normalizing Race Talk

Using the topic of race as a relationship builder, not buster.

Irving recalls how watching school kids—who looked at a canvass of colors swirled together in various paint blobs and then compared the colors on the palette to the colors of their arms—stirred something in her. Even more intriguing was watching them stride back to their classmates to reveal their recipes and compare color swatches, talking about skin color like it was no big deal. “What are you?” one might say to a classmate, holding out the index card bearing a paint swatch on one side and the written recipe on the other. “Two parts coffee, one part cinnamon, and one part peach. What are you?” “Almond and peach, half and half.” They’d hold their arms against the paint color they’d mixed to show off their likeness to the color they’d blended. They compared their own skin tones to classmates’ skin tones by holding their forearms side by side. What a no-nonsense way of talking about skin color.

Reclaiming Her Humanity

Race is not a cause, it’s a part of becoming fully human. —Billie Mayo

Whole Again

Reclaiming her human family, reclaiming herself.

As Irving picked up the notion that race and racism belonged to other people, her mind was trained 180 degrees away from the harsh reality that racism is a problem created by white people and blamed on people of color.

Ironically, only when she tapped into her own vulnerability did she rediscover her inner strength and start listening to her own voice, the one that for years had been trying to tell her something wasn’t right. A spacious and undefended heart finds room for everything you are and carves enough space for everyone else.

Irving recognizes, “I can’t give away my privilege. I’ve got it whether I want it or not. What I can do is use my privilege to create change. I can speak up without fear of bringing down my entire race.”

America is rich with white people clamoring to demonstrate their moral courage and be a part of change that creates the kind of world we can feel good about leaving to our children. We have a choice to make: resist change and keep alive antiquated beliefs about skin color, or outgrow those beliefs and make real the equality we envision.

Tell Me What to Do!

The good news is that everyone can do something to loosen racism’s hold on America. The bad news is that unless you set yourself up for success, trying to do something helpful can actually perpetuate racism. Take time to learn and engage with the problem

Engage

Prepare yourself to adopt an “I don’t know what I don’t know” attitude.